Team 2 Reflections by A.L. Hu, Braham Berg, & Brie Smith

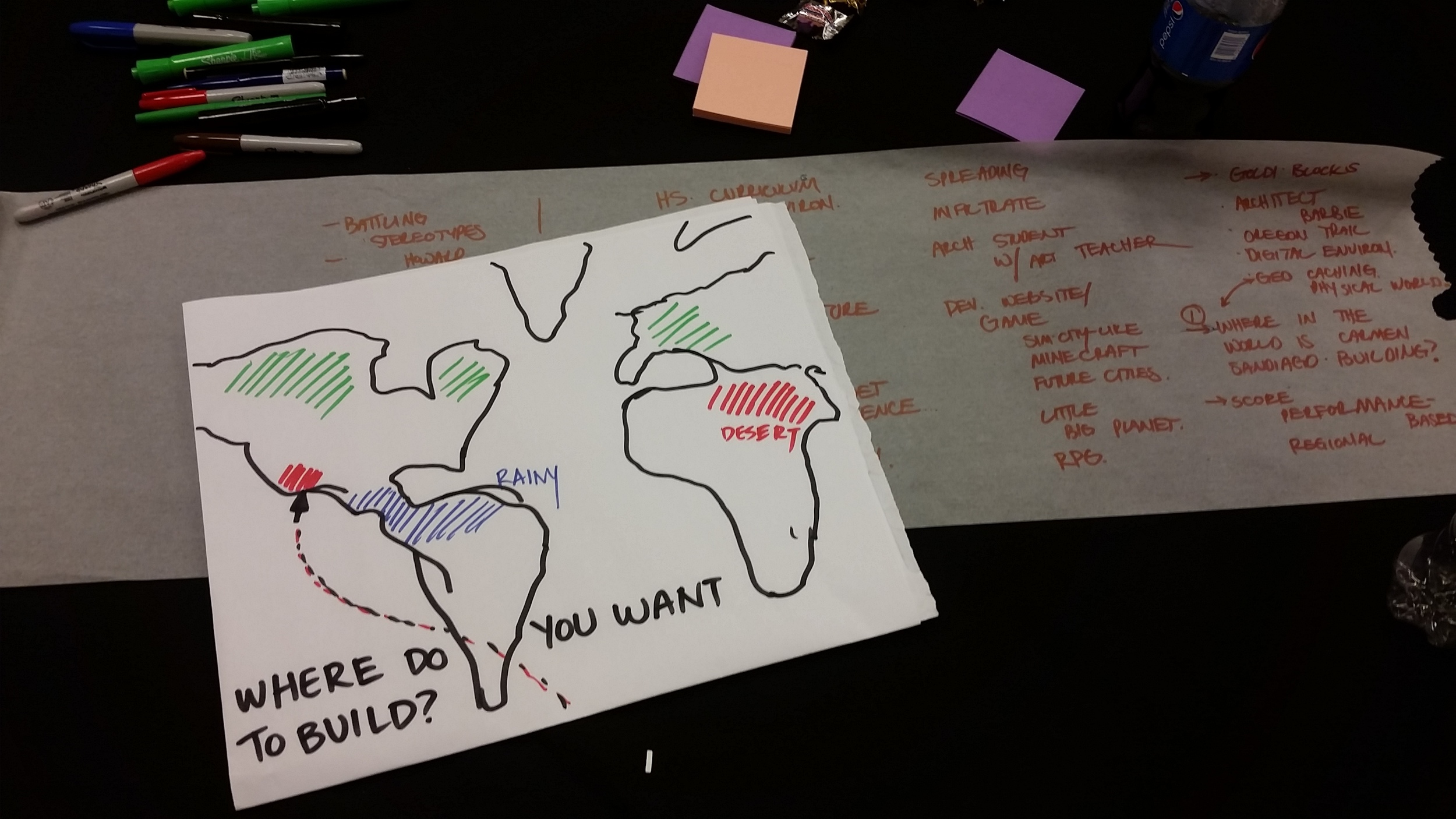

Conceptual Sketch for "Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego Building?"

“The 2016 AIA National Convention promised an exciting program of events (featuring keynotes lectures by Neri Oxman and Rem Koolhaas; and access to intriguing Philadelphia venues); yet, the hands-on nature of the engaging Equity by Design Hackathon was the session that resonated with me most from the Convention experience.

The Convention promised a progressive agenda – geared towards “restructuring” the field and organization towards the future; yet, the Hackathon, in its second year, arguably better addresses this restructuring in practice, and can be wider utilized within the architectural profession in spearheading innovative ideas and change.”

Entering the AIA Convention, the Hackathon was shrouded in mystery and we all went into the session not knowing how things would turnout, but hoping for the best. At its core, the Hackathon is a condensed iteration of the entire design-architectural process. Except, whereas designers have weeks, months, even years to develop their ideas, Hackathon participants have only a few hours. It culminates in a short pitch. Any storytelling tool is fair game.

Rem Koolhaas mentioned in his keynote that architecture moves too slowly to be able to adapt to rapidly changing day-to-day of our World. As a timely and relevant alternative, the Hackathon integrates design and entrepreneurship savvy. In this framework, we, as designers, were encouraged to challenge ourselves in expediting a “design” process we’ve become accustomed to extending (ex. late nights and working on weekends). Through this experience, in the short interval we had to ideate and develop our concept, each group proposed feasible, innovative, alternative solutions, ranging from a work place management – social network (FIM), to an interactive public engagement metric gauge (AGORA), to an educational virtual platform exposing children to the architectural practice, process, and monuments (WHERE IN THE WORLD IS CARMEN SANDIEGO BUILDING?)

THE "EGG" ICE BREAKER

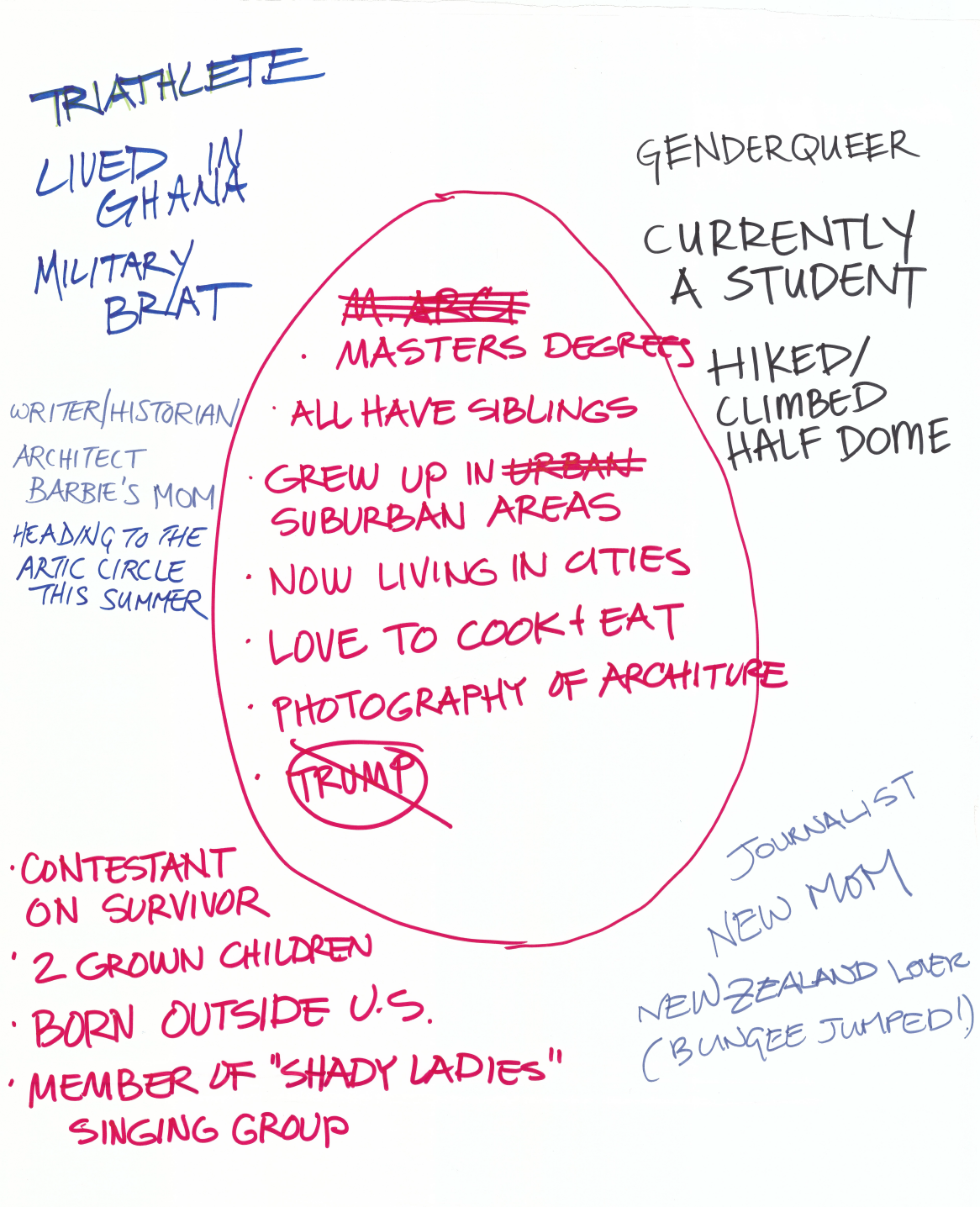

“I appreciated and enjoyed the ‘ice breaker’ exercise — a sheet with one drawn circle. Inside we were tasked to find at least three similarities we had in common, and outside the circle, identify three characteristics and experiences which were unique to each of us. It was a thankful evolution from answering a checklist of labels. With our first attempt at finding a shared experience, we learned that assumptions weren’t absolute, and challenged ourselves to dig deeper. Did we have similar educations? Or education levels? Did we play musical instruments? Have siblings? Have children? What do we like about architecture? How do we feel about Drumph? We identified a dozen unexpected commonalities before we moved onto our uniqueness. By that point, each unique quality was celebrated and shared with stories and explanations. When given the option to move around the room and join a new team, none of us did. Somehow fifteen minutes of populating our circle built enough of a bond we were excited to continue the conversation. For me, equality in design means moving beyond those preconceived notions and working together to celebrate the unexpected and collaborate on a shared goal.”

THE PROMPT – OUR TEAM

Our general task was to design an open-ended product that addressed a defined problem, expressed in a statement, “within the architecture field, related to the architecture field, and outside of the architecture field.”

Team 2: (clockwise) Brie Smith, AIA, A.L. Hu, Braham Berg, Sylvia Kwan, FAIA, and Despina Stratigakos

We had a diverse team spanning nationwide, consisting of AL Hu, a graduate student at Columbia University GSAPP (New York, NY); Brie Smith, a professor at Arizona State University and practitioner with a focus on participatory design (Phoenix, AZ); Sylvia Kwan, Principal of Henmi Kwan and former “Survivor” TV show contestant (San Francisco, CA); and Despina Stratigakos, an architectural historian and professor at SUNY Buffalo (Buffalo, NY). I’m a student at the Tulane University School of Architecture (New Orleans, LA) interested in the intersection of architecture, real estate development, and social entrepreneurship.

DEFINING THE PROBLEM + PROCESS

Our team’s general consensus was to address an issue outside of the profession. Our central themes we hoped to address centered on 1.) perception and 2.) education. In our discussion, we agreed that the public lacks a clear understanding of the architectural profession. The few media portrayals, such as Howard Rourke, do not accurately portray the tasks and responsibilities architects have. On the flip side, some professionals and students channel their inner Rourke-complexities, which does little to de-mystify our profession to the public.

We believe that introducing architecture earlier on in pre-educational, primary and secondary school curriculum was vastly important, and thus could result in a greater awareness and authenticity of architectural practice to a larger populace, particularly targeting young girls.

The Hackathon had a challenging timeline for deliverable tasks. Our group struggled with creating a definitive problem statement because we set out trying to solve two large issues. We worked backwards – sharing extended personal stories to the issues we deemed important to address.

In typical architecture school fashion, our product, vision, and pitch came together in the end. We delivered a coherent pitch, based on personal experience and stories we shared throughout the process. We paired our pitch with a series of quick graphics illustrating the platform adaptation.

OUR SOLUTION

We pitched a game called “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego Building?”, a dynamic and fun way to foster appreciation and awareness for the history and process of architecture in children and teenagers. Through role playing, solving puzzles, and taking on construction projects, game players develop their knowledge of the valuable role architects play in constructing the built environment, especially in the context of climate change. “Where in the World” seeks to change the next generation’s perception of architects and to empower children to pursue architecture as a career.

OUR PITCH

During our pitch, we stressed the importance of expanding the scope and reach of architectural education to include non-architects. After all, everyone is a student of architecture and space in one way or another as all we navigate in three dimensions and seek shelter in buildings.

TEAM 2 PITCH - A.L. Hu, Sylvia Kwan, Brie Smith, Despina Stratigakos, & Braham Berg

And perhaps the education of architects needs to be broadened as well. As a current student who is deeply entrenched in academia and a young practitioner who is keenly aware of many of the profession’s shortcomings, I believe “hacking” and pitching are important skills that expand the scope and reach of architects. Connecting with others on a personal level through storytelling boosts our designs and ideas from mere aesthetics and logistics to a compelling idea that’s part of a larger narrative. The way that we frame our ideas is as important as the idea itself, and that framework is something that should be part of the design process. As architects, we are constantly pitching ourselves and our work for interpretation and valuation by clients and society at large. To change the way we are perceived, we need to think outside of the box and re-design the narrative of our profession--the change begins with us.

TAKEAWAYS

“I arrived in Philadelphia for the AIA Convention not knowing what to expect. The AIA Convention is at once similar to and the polar opposite of graduate school: keynotes, panels, workshops, and networking happy hours centered around architecture are educational and inspiring, but they’re rooted in the practicalities of practice rather than concept and theory. I am grateful that Equity by Design Hackathon was my first experience at the convention because I was reminded that an architectural education is more than just endless production and sleepless nights. Architects need skills beyond drawing and construction knowledge to make connections, make change, and solve problems in the built environment and beyond.

Because of our diverse backgrounds, my teammates and I had radically different ideas as we brainstormed for a problem to solve. While Silvia and Brie brought significant amounts of experience in practice and teaching to the table, Despina offered a depth of historical context and Braham shared his experiences as a student in New Orleans. I lamented the low pay offered to interns and the lack of transparency in regards to salary, experiences that I had chalked up to an unfortunate industry standard that frequently appears in other design professions.

My teammates and I quickly realized that the larger issue at hand is that the way architects are perceived and portrayed in society needs to change”

EQxD Hackathon 2016 Recap - Blog Series

(Catch up here if you missed these earlier posts)

Dear Udo, You were the original Hacker

Meet the 2016 Equity by Design Hackathon Winners - "F.I.M."

2016 EQxD Hackathon Recap: Team 2 - Where in the World...?

2016 EQxD Hackathon Recap Team 1: SWIPE RIGHT! w/ ArchMatch.com

Agora App: A Modern Day Forum For Architectural Practice

How can Architects demystify the built environment?

2016 EQxD Hackathon Jurors: Working with the "A" Team