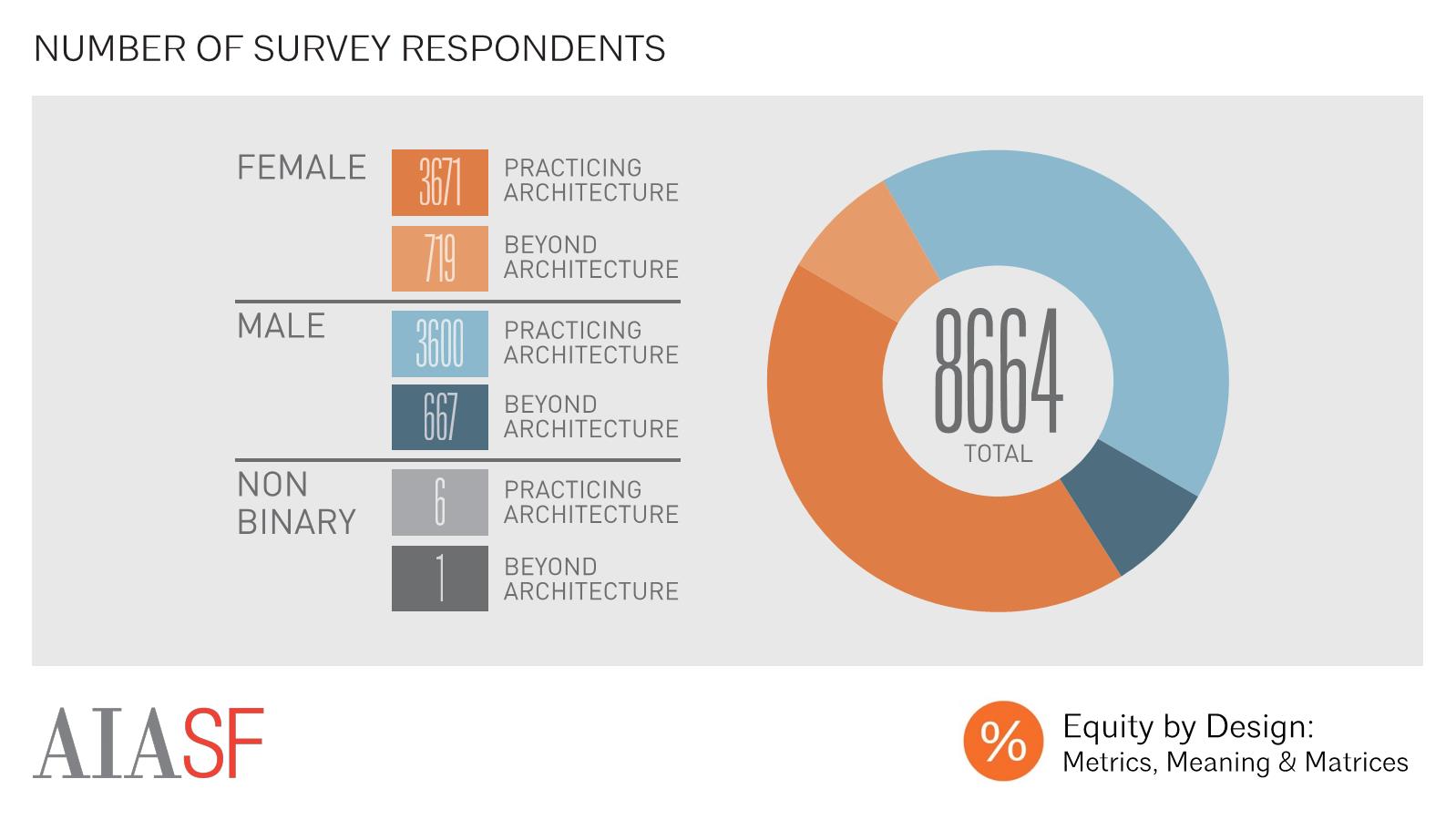

Infographic Slides 2017

Overall Pay Gap

White male respondents made more annually, on average, than white women or people of color. While white men made $96,514, on average, non-white women earned $69,550 on average. It’s important to note, however, that a large part of this difference in annual earnings can be attributed to discrepancies in the average experience level of demographic groups within the survey sample – while the average white male respondent had 18.5 years of experience, the average non-white female averaged 9.0 years, for instance.

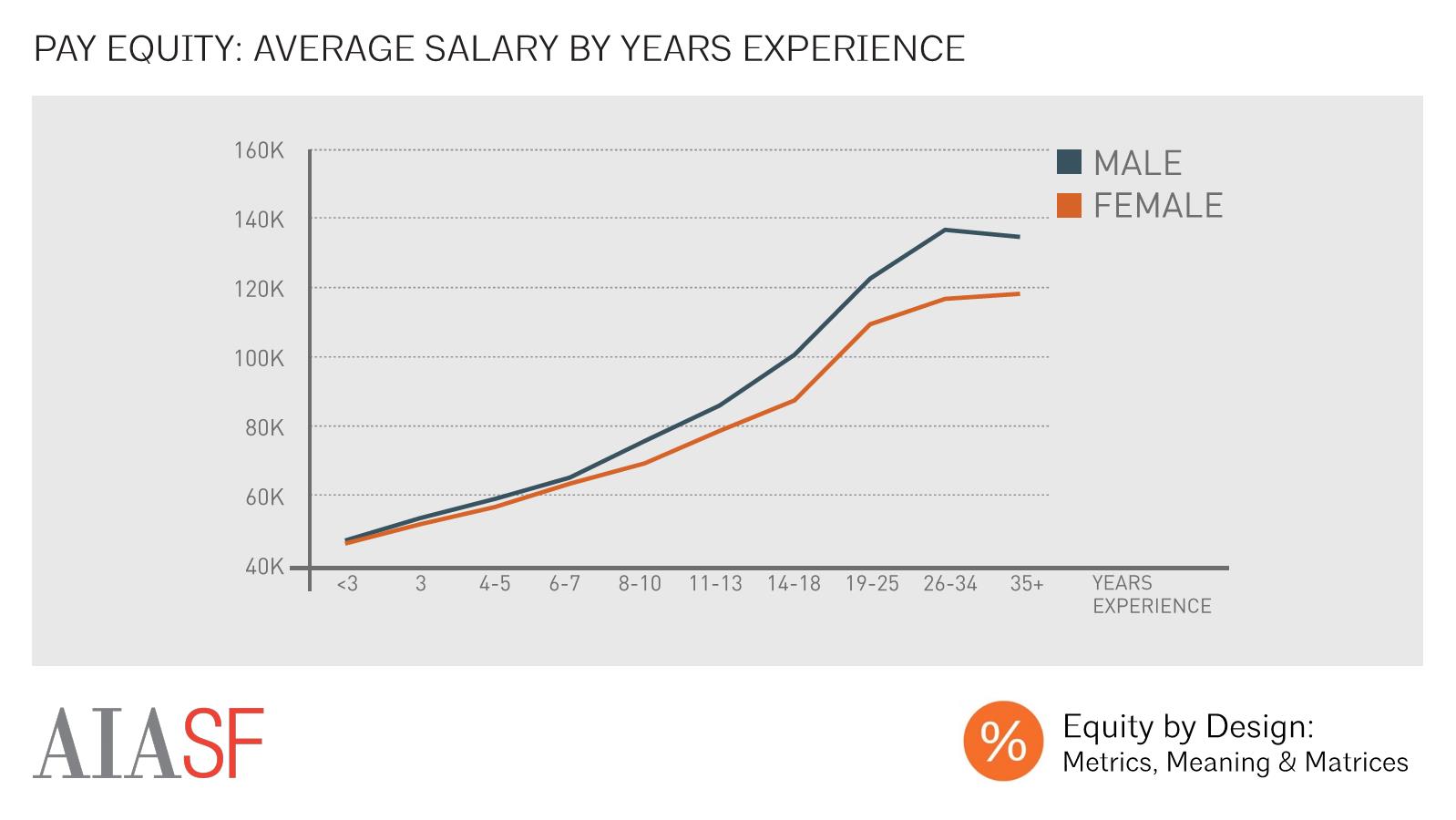

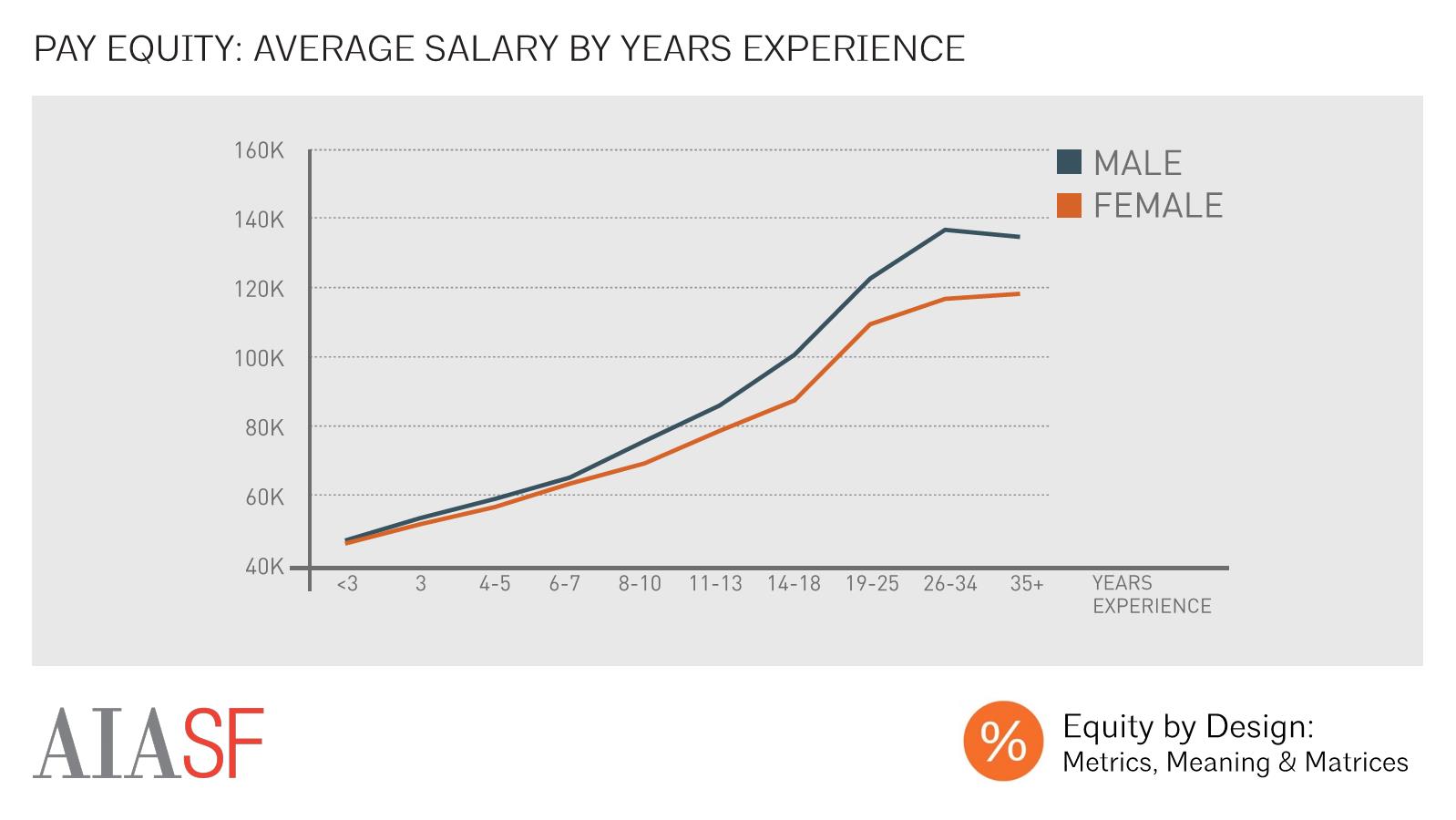

Average Salary by Gender and Years Experience

While the difference in respondents’ average levels of experience accounts for some of the wage gap, significant differences in pay were observed between white male and other respondents even after controlling for years of experience. At every level of experience, male respondents made more, on average, than female respondents, with the largest differences amongst those with the most experience in the field.

Average Salary by Race/Ethnicity and Years Experience

There were also differences in annual earnings on the basis of race, with Black or African American practitioners with 14 or more years of experience earning less, on average, than White, Asian, Hispanic, or multiracial respondents. There were not significant differences in average annual earnings when comparing white and non-white respondents more generally.

How do You Define Success in your Career?

This wage gap is important because earnings played a significant role in the way that respondents evaluated their professional success. “Earnings” were the most commonly cited component of career success, with 42% of females, and 44% of males, stating that they used earnings to define success in their careers.

Practicing Architecture: Top Reasons for Leaving Last Job

Earnings were also tied to decisions about whether respondents stayed at a firm. Amongst those still practicing architecture, “low pay” was the third most commonly cited reason for having left one’s previous employer, after “better opportunity elsewhere” and “lack of opportunities for advancement.” Female respondents were more likely than male respondents to report leaving a position due to low pay.

Beyond Arch: Top Reasons for Leaving Last Job

Amongst those who had left architecture for careers in other fields, earnings were an even more important factor, with “low pay” as the second most commonly cited reason for leaving. The most common reason was “better opportunity elsewhere”. Again, female respondents were more likely than male respondents to report leaving a position in architecture due to low pay.

Average Salary by Career Path and Grad Year

Even though women in the “beyond architecture” population were more likely to leave a position in architecture due to low pay, those who left an architectural firm for a career in another field made less on average than female full-time architectural practitioners within their graduation cohort. Men in the “beyond architecture” population, on the other hand, made more than full-time practitioners at most points in their careers. Simply put, the gender-based wage gap is larger for those who have been trained as architects, but no longer work in an architectural firm, than it is for those working in firms or as sole practitioners.

Part of this large gap in the “beyond architecture” population may be due to the different industries that men and women enter after leaving an architecture firm. While men were more likely to enter high paying fields like construction and real estate development, women were more likely to take positions in education, and the public sector.

Average Salary by Years Experience - Faculty vs. Practitioners

The most common occupation for both men and women in the “beyond architecture” population was architectural education. Within this field, there was a significant, but narrower, par gap, with male architectural educators out-earning women at every level of experience.

Average Salary by Years Experience

The next career dynamic, pay equity, documents the wage gap between our male and female respondents. At every level of experience, our male respondents made more, on average, than our female respondents, with the highest differences at the top of the experience spectrum.

One of the most important ways of looking at the wage gap is to assess whether respondents are receiving equal pay for equal work. Our data showed a gender-based wage gap for every project role, with the largest gap between male and female design principals.

Key Wage Predictors

Several characteristics of one’s job were strongly correlated with either elevated or depressed annual earnings. After adjusting earnings to account for differences in average levels in experience across populations, we found that the strongest predictors of in-sector differences in earnings were related to work setting, and to professional title. Principals and partners made approximately $34,000 more annually than non-licensed designers with comparable experience levels, while titled leaders other than principals or partners made approximately $11,000 more, and licensed architects made approximately $6,000 more. These factors contribute to the wage gap in architecture because female respondents at every level of experience were less likely to hold titled leadership positions within their firms.

Meanwhile, those working in the smallest firms and offices made less money, on average, than those working within larger organizations. Again, because female respondents were more likely than male respondents to work in firms with 20 or fewer employees, the reduced earnings amongst those who worked in these settings contributed to the overall pay gap.

Professional Experience

The single best predictor of earnings was the number of years of experience that one had in the profession, with each year of experience worth approximately $2700 in earnings. There was, however, a great deal of variation in average earnings amongst those with equivalent experience, with the highest degree of variability amongst those with the most experience. The infographic above shows the median salary for each experience level, as well as a shaded area representing the middle 80% of earners in each experience group. This demonstrates that, while there is a large degree of overlap between men’s and women’s salaries, the highest male earners in most experience categories had higher wages than the highest female earners. Conversely, the lowest female earners with more than 10 years of experience made less than the lowest male earners with comparable levels of experience.

Education: Average Salary by Degree Type

The Equity in Architecture Survey indicated that post-secondary degrees have become more common amongst architectural graduates in recent years. This movement towards higher levels of education wasn’t, however, correlated with higher earnings. At every experience level, we found that earnings were comparable for those with and without graduate degrees, meaning that men with Bachelor’s degrees earned more, on average, than women with Master’s degrees.

Average Salary by Licensure Status

One’s professional credentials were also important predictors of salary. Licensed architects made more, on average, than their unlicensed counterparts at every level of experience, with the largest differences in earnings amongst those with the most experience. The salary increase associated with licensure was greater for male respondents than it was for female respondents. Adjusted for experience, licensed men receiving a boost of approximately $8k per year while licensed women received a boost of only $4k per year.

Experience-Adjusted Wages by Professional Org Membership

Membership in a professional organization was also correlated with increased earnings for respondents of both genders. AIA, NCARB, and USGBC members made more than those who did not belong to any professional organizations at every level of experience. It’s worth noting that this correlation doesn’t necessarily prove that membership in a professional organization increases one’s earning potential. Each of these organizations has annual dues, which may be easier for those with elevated earnings to pay.

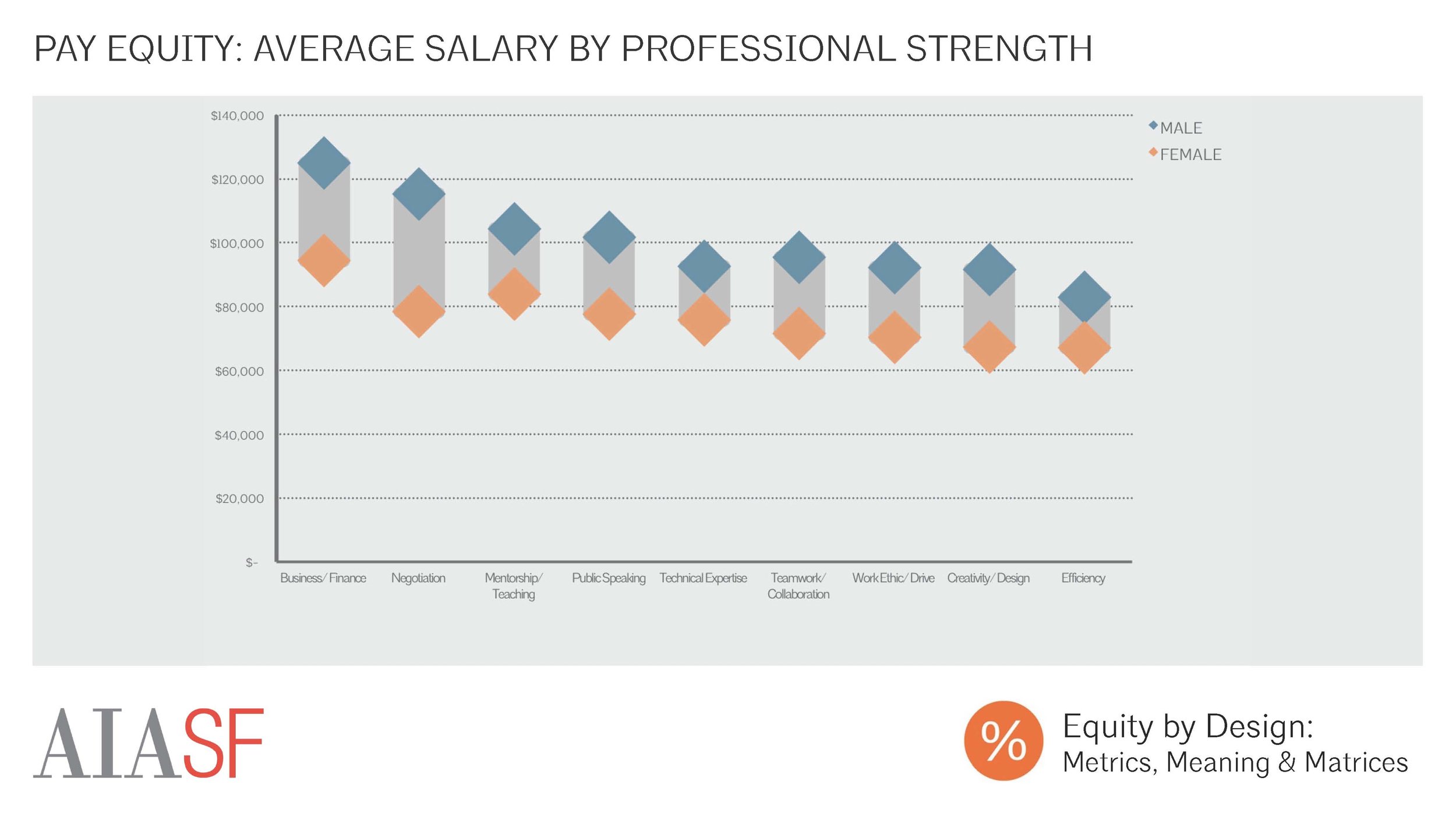

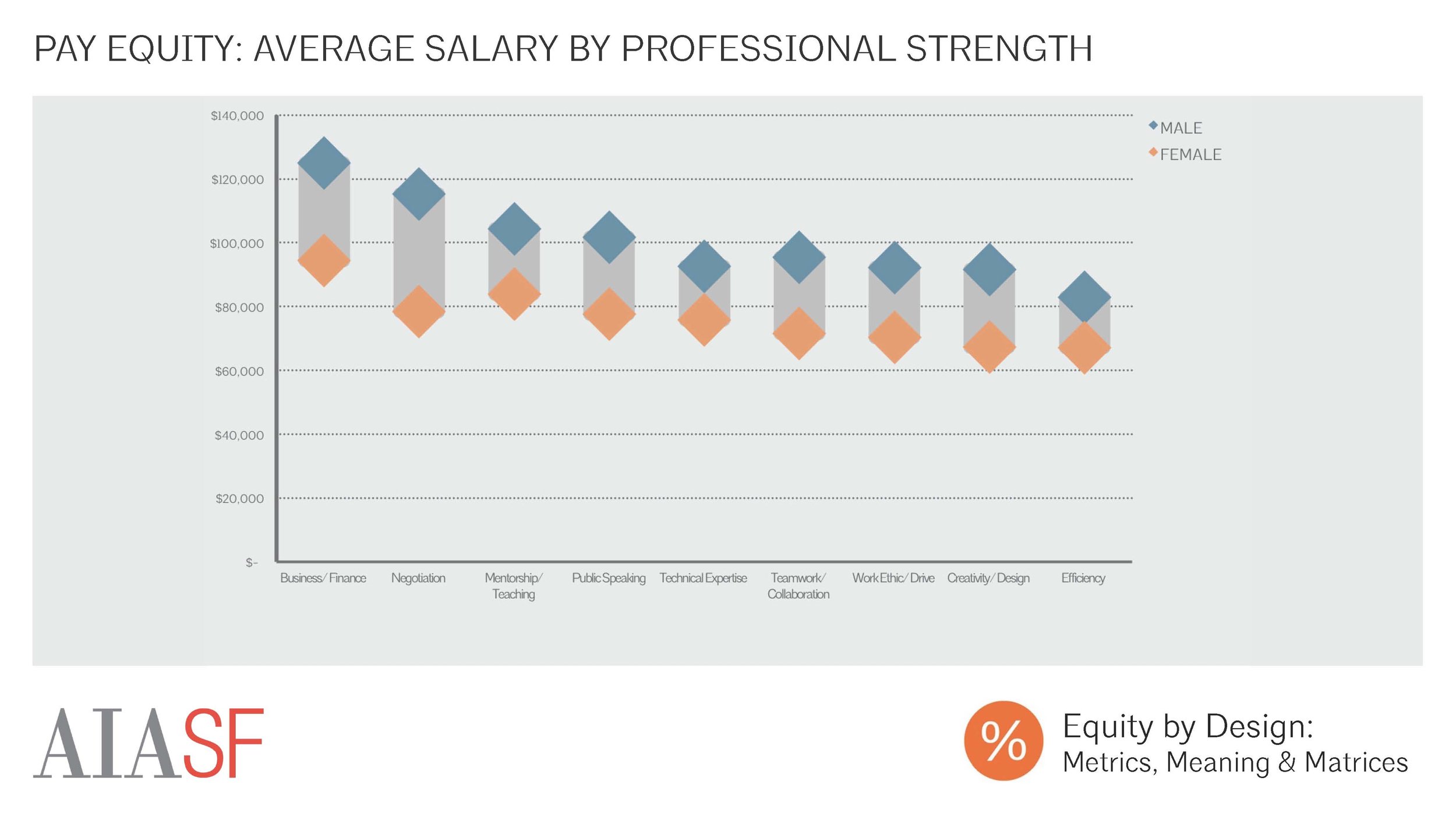

Average Salary by Professional Strength

Respondents’ self-identified professional strengths were also correlated with differences in earnings. Those who reported specialized strengths in “business and finance”, “negotiation”, or “mentorship and teaching” averaged the highest earnings. Meanwhile, those who listed more general traits like “work ethic and drive”, “creativity or design”, or “efficiency” as their greatest strengths made the least, on average. The largest gender-based earnings gap was between men and women who listed “negotiation” as a strength, with skilled male negotiators earning $37K gross, or $15K experience-adjusted, more on average than skilled female negotiators.

Average Salary by Number of Firms and Years of Experience

While there is anecdotal evidence that young practitioners routinely move between firms in pursuit of salary increases that exceed typical annual raises, the data from the 2016 Equity in Architecture demonstrates no significant correlation between one’s history of switching firms and average earnings.

Average Salary by Tenure at Firm and Years Experience

Meanwhile, the data shows that, amongst those with 8 or more years of experience, a longer tenure at one’s current firm was associated with higher pay. Together, these statistics demonstrate that, on average, staying with a single firm over a long time period is more financially rewarding than frequently moving between firms.

Experience-Adjusted Salary by Geographic Location

The geographic location of one’s firm was significantly correlated with both overall earnings, and with the size of the wage gap. Those working in major cities made more, on average, than those working outside of these metropolitan areas. After normalizing average salaries in the five most common locations from the survey to the national average of 14 years of experience, the highest average salaries were observed in San Francisco ($105,031 per year for men and $93,015 per year for women) and New York City ($102,718 annually for men and $94,331 for women).

The gender wage gap also varied considerably by office location, largely because men’s salaries varied considerably by geographic location while women’s salaries were more consistent across regions. The largest salary wage gaps were generally observed in the locations where men’s average salaries were highest, while smaller gaps were observed in locations where men’s average salaries were lower. In San Francisco, where experience-adjusted male respondents’ salaries were the highest in the nation, the average experience-adjusted female made $0.89 for every dollar a man earned. Meanwhile, in Seattle, WA, where the average experience-adjusted salary was actually lower than the national average, the average experience-adjusted female actually made more than the average experience-adjusted male -- $1.01 for every dollar that a man earned.

Average Salary by Years Experience - San Francisco vs. National

Similar to the national pattern, the wage gap in top metropolitan regions was at its widest amongst those with the most experience. In San Francisco, where the average wage gap was wider than the national average, men and women with 10 or fewer years of experience made comparable amounts, while, the wage gap amongst those with more than 10 years of experience was considerably larger than the national average. Much of this difference can be attributed to the fact that experienced male respondents working in San Francisco made considerably more than the national average, while experienced women working in this location made only marginally more than the national average salary.

Average Salary by Firm Size

We also saw that firm size was correlated with wages, with those working in the largest firms making the most money on average. However, the relative difference in wages based on firm size was much smaller amongst female respondents than it was amongst men.

Experience-Adjusted Wages by Firm Size

Smaller, but still significant, differences in average annual pay were observed within most size categories after adjusting the data to account for differences in average experience level between male and female respondents. Again, the largest pay gap was observed within the largest firms. Male respondents working within these settings tended to make far more than the national average salary, while female respondents saw only minor increases above the average female salary for opting to work in these settings.

Average Salary by Project Role

One of the most important ways of looking at the wage gap is to assess whether respondents are receiving equal pay for equal work. Our data showed a gender-based wage gap for every project role, with the largest gap between male and female design principals.

Average Wages by Project Responsibility

Male respondents also made more, on average, than female respondents with equivalent project responsibilities. This was true for every project responsibility listed in the survey. The largest gross difference observed was for management of client relationships (pay gap of $26k/year gross, or $6k experience adjusted). The largest experience-adjusted pay gap was observed amongst those responsible for design leadership (pay gap of $22k/year, or $7k/year experience adjusted).

Average Wages by Office Management Responsibility

Female respondents made less, on average, than male counterparts with similar office management responsibilities. The largest gaps were observed between those responsible for marketing and new business development (pay gap of +$29k gross, or $9k experience adjusted), and strategic planning (pay gap of +$27k gross, or $9k experience adjusted)

Experience-Adjusted Salary by Work-Life Flex Importance

A side-by-side comparison of respondents’ experience-adjusted average salaries based upon gender and response to the question “How important is it to you that your job provides work-life flexibility, integration, or balance?” demonstrates that those who place higher importance on work-life flexibility, integration, or balance make less, on average, than those who view the issue as less important. Moreover, women’s average earnings vary considerably based on their response to this question, while men’s salaries vary more subtly based on work-life importance. This suggests that work-life prioritization is correlated with salary, and that decisions to prioritize work-life flex impact women disproportionately.

Experience-Adjusted Salary by Work-Life Benefits Used

Use of work-life flexibility benefits was correlated with earnings, with the use of benefits that entailed working fewer hours correlated with decreased earnings, and the use of benefits that facilitated working outside of the office correlated with increased earnings. Women averaged lower earnings than men, regardless of which benefits they used.

There was an interesting gendered difference in the pay of those who used schedule flexibility benefits like comp time, core hours, and compressed schedules. Each of these benefits allows a user to trade time away from the work during some regular business hours for work conducted outside of the normal 9-5 workday. When adjusted for experience, men who reported using these benefits made more than men who said that they hadn’t used any work-life benefits. Meanwhile, women who used these benefits earned the same amount, or slightly less than women who reported using no work-life benefits.

Average Hourly Wage by Years Experience

All of this suggests that the average number of hours that one works, when coupled with experience level, is highly predictive of wages. In fact, respondents’ calculated hourly wages, which were derived from the average number of hours that a respondent reported working per week and reported annual earnings, were comparable for men and women with 10 years of experience or less. However, there were significant gender differences in hourly wages amongst more experienced professionals, with women earning less money per hour than male respondents.

Average Salary by Caregiver Status

Parenthood was an important predictor of earnings, largely due to differences in mothers’ and fathers’ reported caregiving responsibilities, and the work settings and schedules that they chose in order to accommodate these responsibilities. We saw that, while men and women without children had similar average salaries by years of experience, fathers made more, on average, than men without children, while mothers made less, on average, than women with children.

Average Experience-Adjusted Salary by Reason for Alt Schedule

We saw additional evidence for the idea that childcare places an undue financial burden upon working women when we compared the experience adjusted salaries of men and women who reported working an alternative schedule (part time, comp time, core hours, or compressed) based on their reason for working that schedule. Men who chose an alternative schedule to accommodate childcare made the most money, on average, while women who worked one of these types of schedules to accommodate childcare earned the least, on average.

Average Salary by Experience When Oldest Child Born

The timing of the birth of one’s child relative to one’s professional development was significant. By subtracting respondents’ children’s ages from their level of experience, we were able to approximate their level of experience at the time of the birth of their children. This analysis revealed that fathers’ salaries were comparable to, or exceeded, those of their counterparts without children, no matter when in their career their oldest child had been born. Those who had become fathers when they had four or fewer years of experience made less, on average, than those who had become fathers later in their careers. Meanwhile, mothers tended to make less than their counterparts without children at most stages in their careers. The only exception was amongst women who had become mothers with 8-10 years of experience. These women made comparable amounts to, or even more than, their counterparts without children.

Average Salary by Experience When Youngest Child Born

Amongst female respondents, patterns in earnings related to when one’s children were born were even more significant when we considered a respondent’s experience level at the time of the birth of her last child. Women whose youngest child was born when they had seven or fewer years of experience in the field made substantially less, on average, than women without children as well as women who had finished giving birth later in their careers. This difference in earnings was at its largest amongst those with the most experience, suggesting either that the penalties related to motherhood were much more significant in the past than they are today, or that the impact of having children at the beginning of one’s career lingers late into one’s career. Like their female counterparts, men who had finished having children early in their career made less, on average, than fathers who had amassed more professional experience before the birth of their last child. However, these differences in salary on that basis of work-life sequencing were far smaller for fathers than they were for mothers.

The kinds of attention that firm leaders pay to their employees are strongly correlated with employee salary. After adjusting for experience, individuals who received feedback on their embodiment of firm values, their leadership traits, and their business development skills during the performance review process made more, on average, than those who did not receive this type of feedback. Meanwhile, those individuals who reported that their firm did not have a performance review process, or who did not know the criteria for performance evaluation, made less, on average. In all cases, the performance review process was more strongly predictive of male respondents earnings than of female respondents’ earnings.

As discussed in the last article, individuals’ schedules were strongly predictive of earnings. Respondents of both genders who reported that they never worked overtime made substantially less, on average, than those who did reported working overtime, with male respondents who never worked overtime averaging about $23K less than those who did, and women who never worked OT averaging $17k less. Meanwhile, female respondents faced a steeper penalty for working a part-time schedule, with part-time female employees averaging $13k less than full-time female employees while part-time male employees averaged $8k less than full-time male employees.

Receiving career guidance from a senior leader within one’s own firm was also strongly correlated with higher annual earnings. Amongst respondents with 8 or more years of experience, the wage difference associated with mentorship was larger for male respondents than for female respondents, suggesting that men may reap larger financial rewards from their mentor-mentee relationships with firm leaders.

Respondents who indicated that their had a sponsor, or someone who advocated for them, within their firm also earned more, on average, than those who did not have such a person. Once again, the identity of one’s sponsor was a significant predictor of earnings. In this case, however, having a peer advocate was at least as beneficial as having an advocate in management, especially amongst more experienced respondents. This may be because many respondents with more than 18 years of experience were in management themselves, suggesting that even firm leaders need peer advocates within their organization’s management structure. More analysis would be required to explore why respondents with peer advocates made more, on average, than those with advocates in mid-level management.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, female respondents were actually more likely to indicate that they had negotiated their salary in the past. Most of this difference, however, can be attributed to similar difference in male and female respondents’ likelihood of saying that they had always been satisfied with their salary offers. In other words, women were more likely to negotiate, but only because they were less likely to be offered a satisfactory wage in the first place.

Amongst those who had negotiated their salary, respondents of both genders had high rates of success, with roughly ⅔ of respondents receiving either the full amount that they had requested, or an increased offer that was smaller than their initial bargaining position. Male negotiators, however, were slightly more likely to receive the full amount that they had requested, while female negotiators were slightly more likely to receive a partial amount.

Compared to those who were dissatisfied, but did not negotiate, and even to those who had always been satisfied with their salary offers and had never felt the need to negotiate, negotiators of both genders made more, on average, at nearly every level of experience. Compared to those who had always been satisfied, these increases were quite modest, however, for female negotiators. Male negotiators with more than 13 years of experience, on the other hand, made significantly more than those who had always been satisfied with their earnings. This suggests that female negotiators were adept at negotiating for earnings that were considered “fair”, while male negotiators tended to pull in salaries well above the average.