By Michael Thomas

1. Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

My name is Michael Thomas. I am a labor and employment attorney with the law firm Ogletree Deakins in San Francisco. My practice focuses on class actions and employment litigation. I am also part of our Pay Equity group and I conduct workplace trainings on implicit bias and diversity.

2. Why did you choose to study law?

I grew up a poor, African-American male raised by a single mother. At a young age, I knew that I was different because of my race and class. I also know now that people often viewed me and I often viewed myself based on stereotypes and biases inherited through socialization and from prior generations.

Law is a powerful tool to guide society in changing perceptions and beliefs that are formed by stereotypes and biases. Examples of this in practice include the legal battles to racially integrate the military and schools and legalize interracial marriage and same sex-marriage. A more recent example is a set of laws designed to correct pay disparities based on race, gender and ethnicity.

3. What inspires you on a daily basis?

I am inspired each day by my ability to be curious about my potential. I strongly believe that to take a step forward, we often have to step back and unlearn what prevented us from moving forward.

Michael, bottom, with his brother.

I grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My grandfather was one of the first African-Americans to integrate the steel mills. He had to fight racism to do that. He was also one of the first African-Americans to purchase a home in a certain part of Pittsburgh. He had to fight racism to do that too. He spent so much of his life fighting against racism that he became a hard and unemotional man. My grandfather expected my father to be the same way in order to function in a predominantly white world. Influenced by my father’s family, I grew up in the same environment where the expectation was that the world was hostile because of my race and I could not show vulnerability.

I was also socialized to assume that “whiteness” was the norm and the standard to follow and strive towards. I learned at an early age that if I wanted to function and to succeed in society, I had to learn how not to be seen as “black,” how not to reveal or recognize my authentic self, and how to not show vulnerability.

This strategy was effective at different points in my life. However, as an adult, to get feedback on how to grow and mature in career, life, and love, I have to understand my authentic self and my needs. I have had to step back and let go of false beliefs about myself to step up and step forward. It all begins with being curious about my potential. Remaining curious inspires me.

4. What are three of your most influential projects and why?

My three most influential projects: 1) developing a Mindful Mentoring Program that connects adults with youth at risk via a mindfulness practice; 2) working with Inclusion Ventures to develop a comprehensive pay equity audit and implicit bias training; and 3) speaking at Inclusion 2.0 on “Diversity, Inclusion and Intergenerational Trauma.” Why? All three are creations of my authentic self.

5. What is the greatest challenge/difficulty that you have had to overcome in your professional career?

Learning to let go of fear and beliefs that are limiting.

6. What do you believe has been one of your greatest accomplishments to date? Why?

Michael's depiction of himself, practicing yoga.

I completed a yoga certification training with the Niroga Institute in Oakland, California. Niroga teaches Raja yoga, the yoga of mindfulness. In Raja practice, yoga poses and breathing techniques come together to prepare your body and mind for focus and moment to moment awareness.

Why do I consider this one of my greatest accomplishments? During my practice of yoga, I stopped to observe my black skin and the physical and mental harm it receives from stereotypes and bias. It was the first time I can remember that as I made those observations and my mind went into fight or flight mode and I wanted to escape the discomfort, I could not. Instead, I had to stay in my posture and focus on my breath without reacting. In that experience I learned acceptance and forgiveness, and how to not respond to false thoughts or beliefs. At that point I was able to direct my attention inward, without judgment or blame.

Focusing the mind on breathing and bodily sensations through gentle movement activates the prefrontal cortex, or the noticing part of the brain. The noticing part of the brain, when activated by my yoga practice, allows me to observe that I am not my fears or the biases projected by others and myself. It allows for more self-regulation and conscious decision-making in the moment.

Now, after my training in Raja yoga, I can show vulnerability and empathy towards others without fear. Empathy and vulnerability allow for greater decision-making out of curiosity instead of fear. Curiosity leads to discomfort. Discomfort leads to growth and change.

At some point we have to stop blindly moving forward and stop and make courageous decisions to treat ourselves and each other differently even if it means embracing fear and the unknown.

7. If you could go back in time, what would you tell your 24 year-old self?

Don’t be afraid. You belong.

8. What is the best advice that you ever received and how does that apply today?

BK Bose is the Executive Director of the Niroga Institute. He frequently asks the question, “What separates you from freedom?” I think of that question if I feel I am making decisions out of fear and not love or kindness. It allows for better decision-making.

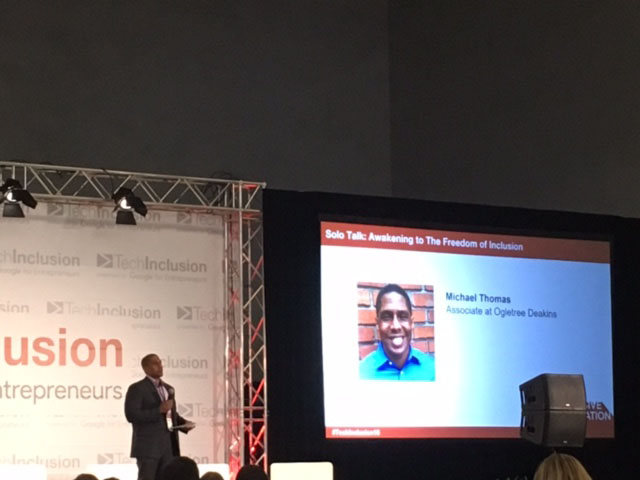

Speaking at Tech Inclusion 2.0 on "Diversity, Inclusion and Intergenerational Trauma."

9. How do you see the law profession changing in the next 10 years? What would your role be in the future?

The most important characteristic for lawyers to cultivate will be empathy. The practice of law focuses on logic and reason. Both are important. Both are also devoid of feelings and emotion. As a result, lawyers often cause harm and lack creativity because we are not using the creative side of our brain. Empathy is the pathway to creativity. Creativity is the pathway to innovation. Innovation will assist lawyers in being of greater service to our clients and to society. It all begins with empathy.

10. We have heard that while the general public respects lawyers, they have little knowledge about what they do. Do you have any thoughts about how we can bridge the gap?

Law school should be more affordable and accessible. When there are significant barriers to entry, the legal profession becomes exclusive and accessible only to a small portion of the population. The law should be more accessible for people to either become a lawyer or for people to know a lawyer.

About our INSPIRE% Contributor:

Michael D. Thomas was a panelist for our EQxDisrupt Workshop in February 2017. His work as a Lawyer in equitable practice areas such as pay equity, mitigating bias in hiring and promotion processes and his thoughts on mindfulness and healing lead us to ask him to contribute to this series. Even though he is practicing in another field, we value advocates for equitable practice and the lessons that we can learn from their journey as well.

Michael is an Associate with the global law firm Ogletree Deakins in their San Francisco office. He represents employers in all aspects of employment law. He also works with employers on diversity and pay equity issues. Michael has studied mindfulness, meditation and yoga with a focus on healing and self-regulation. Recent publications include “Preventing Workplace Violence by Examining Trauma and the NFL” which incorporates mindfulness, meditation and body awareness in preventing workplace violence, and “How Employers Can Root Out the Influence of Unconscious Bias in Compensation Decisions.” Recent speaking engagements include: Inclusion 2.0, “Intergenerational Trauma, Diversity and Inclusion;” Tech Inclusion Conference, “Awakening to Inclusion;” Association of Corporate Counsel event at Google, “Best Practices for Promoting Fair Pay;” Kaiser, Continuing Legal Education, “Implicit Bias” panel and lecturer, Berkley School of Law, “Mindfulness to Disrupt Suffering and Bias.” He has a B.A. from Bucknell University and a J.D. from Boston College.