By Annelise Pitts, AIA, Equity by Design Research Chair

What is "job-person fit," and why is it so important to career success? Clinical psychologists Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach argue that job-person fit is assessed using a web of interrelated career perceptions that have been shown to predict whether a respondent will become burned out or engaged in the future, and even whether they will ultimately leave their jobs. Anecdotally, those who work in jobs that they love, and in workplace cultures where they feel included and valued have found a good fit.

Within architecture, fit can be elusive, with professionals from underrepresented groups and more junior employees facing particular challenges in finding the right fit. Within these groups, career perceptions tended to be less positive than they were for white men and more established professionals, and turnover rates tended to be higher. Even though underrepresented groups tended to face greater challenges relative to fit, the survey highlighted key factors that motivated or predicted "fit" regardless of personal identity. Firms that understand and respond to these factors may be able to boost career satisfaction and retention for all employees.

Overall, we found that decisions to join and to stay at firms tended to be guided by respondents’ sense of alignment with a firm’s work, values, and culture. Those who were able to report that their work was meaningful and rewarding and relevant to long-term goals, and those who built strong relationships with peers and mentors at work through friendships, training, and shared decision-making were most likely to report that they were satisfied with their work culture, and were planning to stay in their current positions. Please use the arrows in the upper right-hand corner of slideshows below to learn more.

Joining a Firm

We found that the top three reasons that respondents accepted jobs were “quality of projects”, “learning opportunities”, and “firm reputation.”

Respondents tended to cite similar reasons for taking jobs, although women were slightly more likely to prioritize work-life flexibility, while men, and especially men of color, were slightly more likely to prioritize advancement opportunities. Respondents of color were more likely than white respondents to cite salary offered as a primary motivator in choosing their job.

White male respondents were the least likely of any group to report taking a position based on “learning opportunities.” This difference, however, is largely explained by the difference in median experience level between white male and other respondents, as those starting their careers were more likely to report taking their jobs to capitalize on learning opportunities.

Respondents reported working in firms ranging in size from sole proprietorships to large firms with over 1000 employees. The plurality of respondents worked in firms with fewer than 20 employees. Female respondents were more likely to report working in firms with fewer than 20 employees, while male respondents were more likely to report working in the largest firms.

Respondents’ firm size was strongly correlated with their top reasons for taking their current jobs, with those in the smallest firms most likely to say that they had taken their jobs because they afforded work-life flexibility and because they shared values with their firms. Those working in the largest firms, meanwhile, were significantly more likely than those working in small firms to report that they had taken their position because of their firm’s reputation, project quality, salary offered, and advancement opportunities. These patterns are mirrored in the lived experiences of employees, with those working in the smallest firms reporting the highest average satisfaction with their work-life flexibility. Meanwhile, average salaries were largest within the largest firms and those working in the largest firms tended to have the most positive impressions of their firms’ promotion processes.

There were also significant differences in firm size on the basis of race, with white, latinx, and multi-racial respondents most likely to work in firms with fewer than 20 employees. African American or Black respondents were slightly more likely to work in small and medium-sized firms, but had a similar overall distribution of firm sizes. Asian respondents, meanwhile, were most likely to work in medium firms, with 50-249 employees, and were also more likely than others to work in large and extra-large firms.

Career Perceptions

On average, male respondents’ career perceptions were more positive than those of their female counterparts. When asked about the relative positivity or negativity of their career perceptions across 14 categories from “work –life flexibility” to “promotion process ”to their likelihood of staying at their job for the next year,” male respondents’ average perceptions were more positive than female respondents’ in every category. The largest gender gaps indicated significant differences between men’s and women’s likelihood of feeling energized by their work (male respondents 7% more likely), likelihood of “having a seat at the table”, or being included in one’s firm’s decision-making process (male respondents 6% more likely), and likelihood of planning to stay in one’s current job for the next year (male respondents 6% more likely).

There were also areas of work-life that tended to be viewed more positively or negatively by all respondents: average perceptions of autonomy, satisfaction, and confidence tended to be most positive for respondents, while respondents’ average perceptions of their firms’ promotion processes, their work-life flexibility, and their workloads were least positive, on average. Male respondents perceptions were more positive, on average, than female respondents’ perceptions in each of these categories. We did not observe significant differences in career perceptions on the basis of race or ethnicity.

Workplace Culture and Shared Values

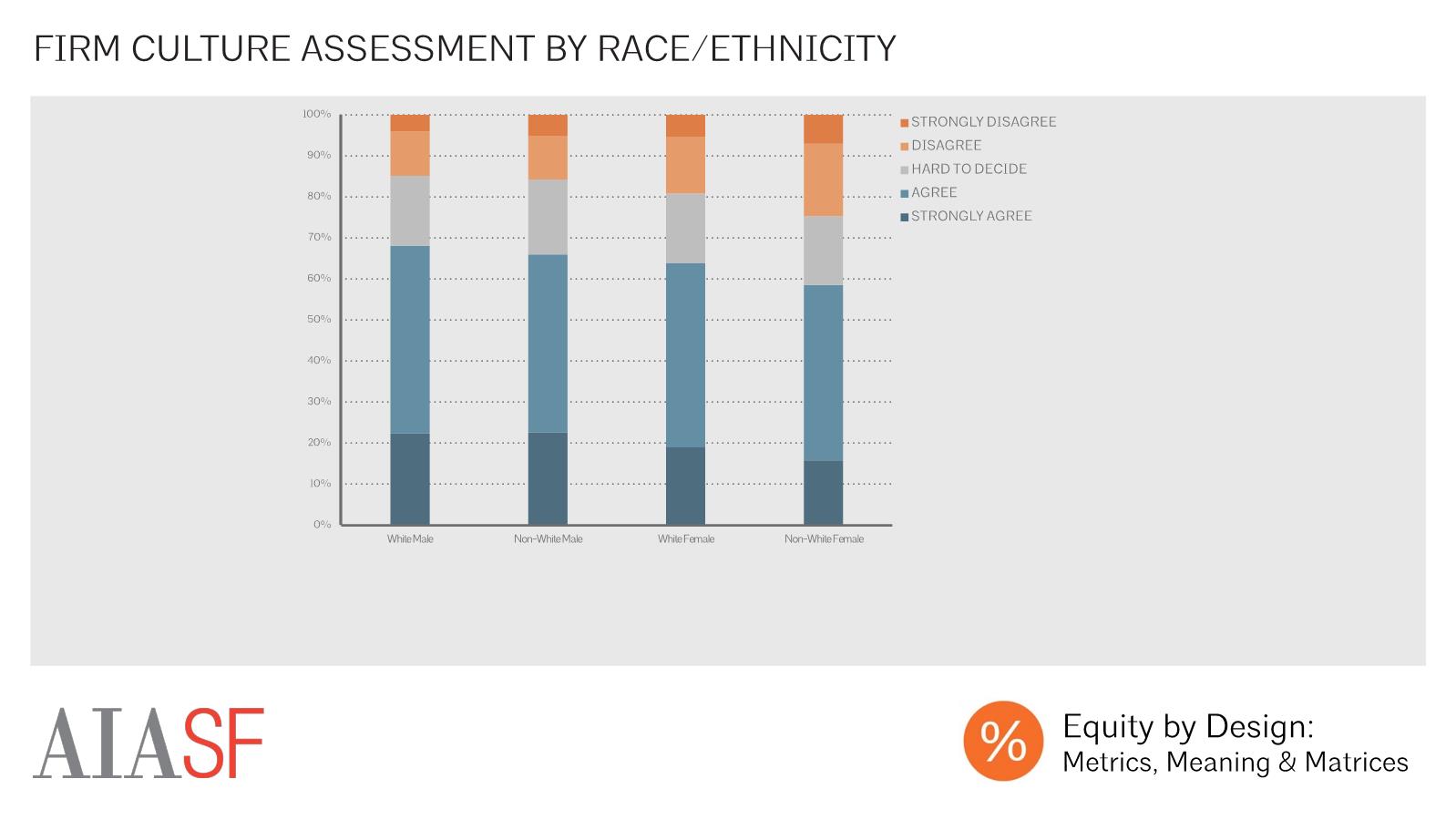

There were also significant differences in career perceptions in several areas on the basis of race as well as gender. White men were most likely to agree with the statement “I am satisfied with my workplace culture,” with men of color, white women, and women of color each successively less likely to agree with this statement.

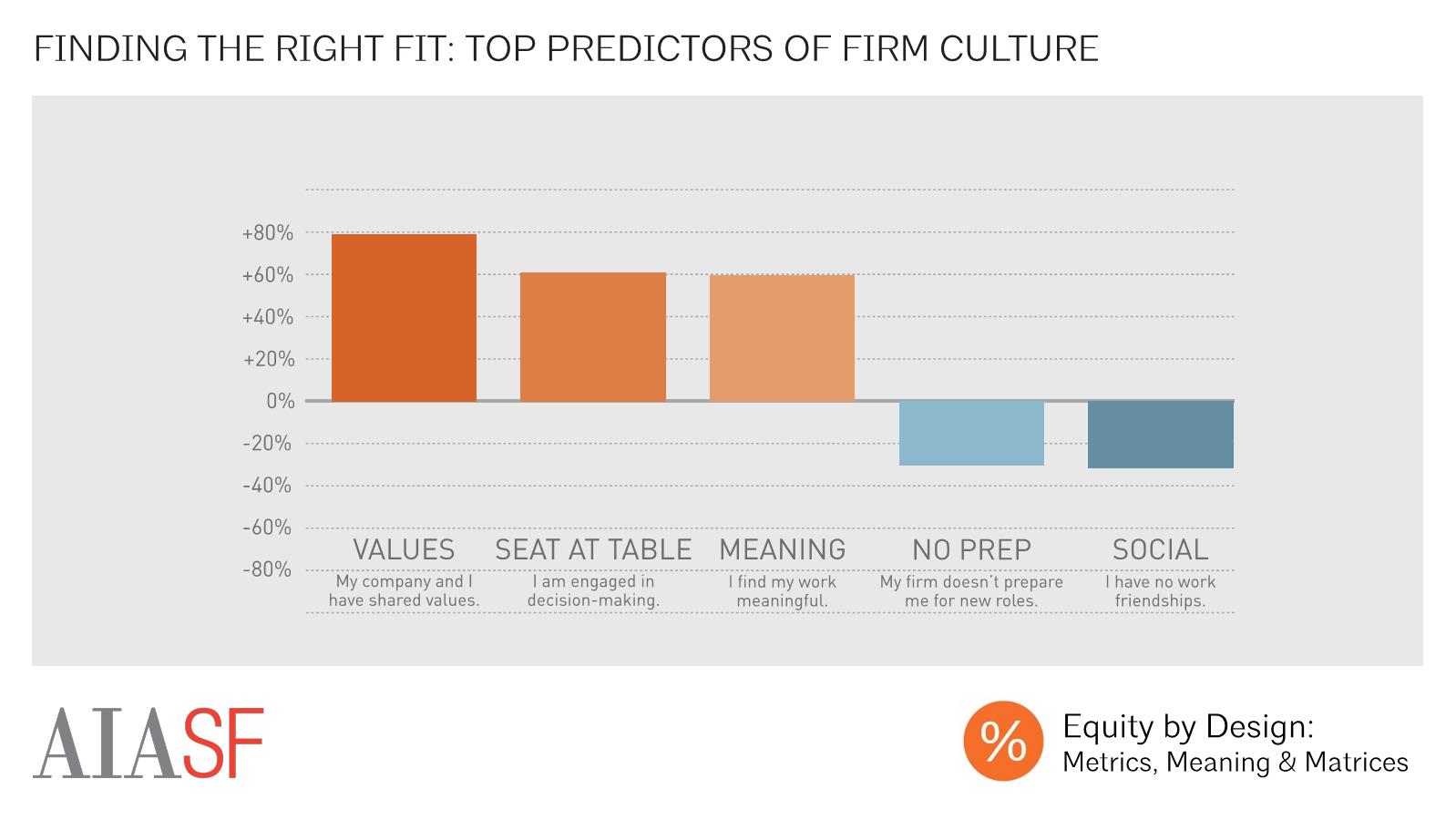

While workplace culture was viewed more negatively on average, by female respondents and by respondents of color, neither gender nor race were top predictors of whether a respondent had a positive assessment of their culture. Instead, the beliefs that a respondent shared values with their employer, that they were engaged in the decision-making process, and that they found their work meaningful and rewarding were associated with positive assessments of firm culture. Female and non-white respondents were less likely than white male respondents to agree with each of these statements. This suggests that equity issues are often multi-faceted, and that organizations must address equity holistically by looking beyond issues of representation to address issues of access, relationships, and culture.

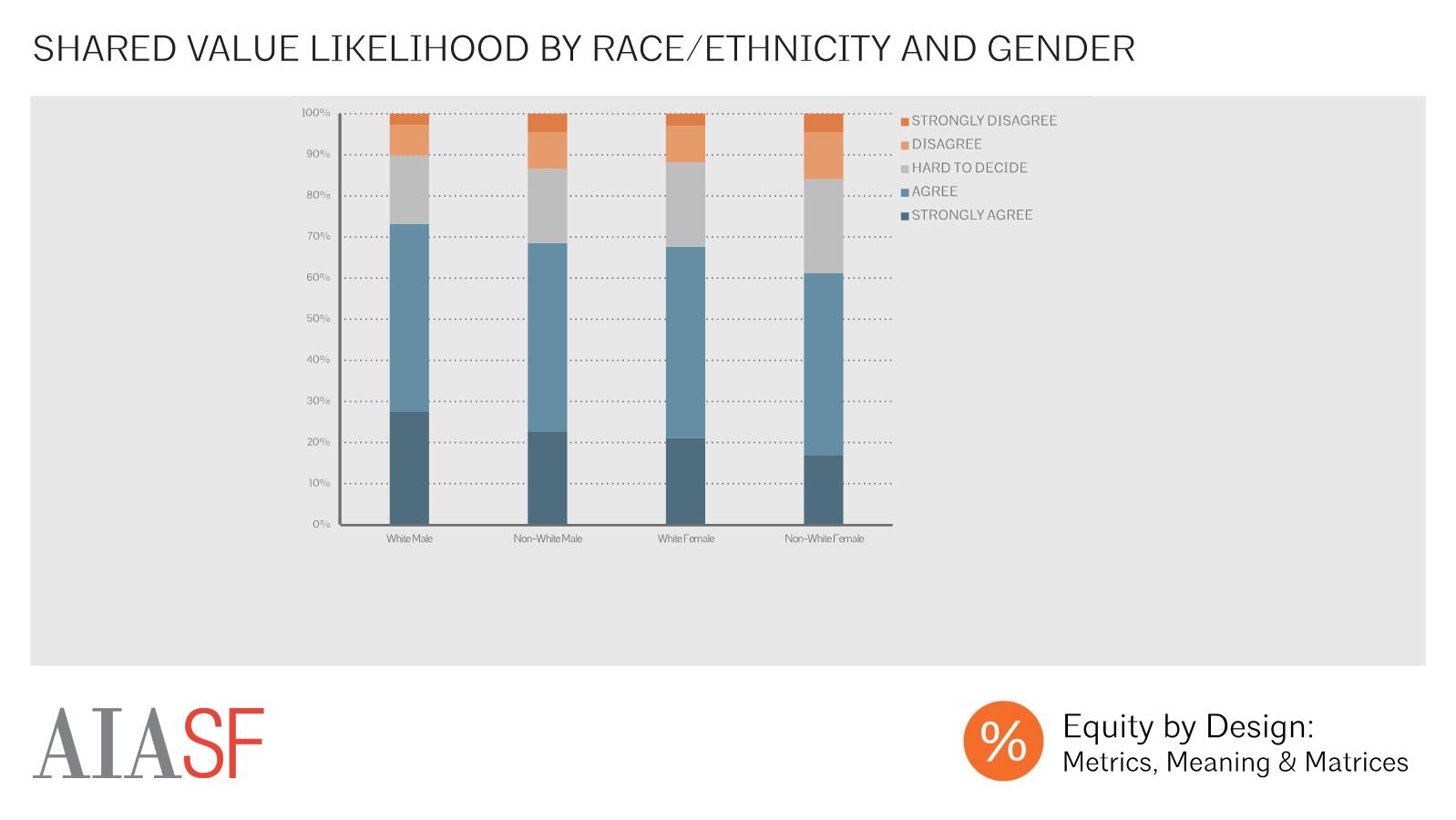

The top predictor of whether or not a respondent was satisfied with their workplace culture was the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement “My values and my company's values are alike.” According to a study conducted by Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach, sharing values with one’s company also tends to be the greatest overall predictor of job-person fit, and whether an individual will stay with their current company and be engaged in their work. It’s unfortunate, then, that white male respondents were significantly more likely than others to report that they shared their companies’ values, with women of color least likely to agree with this statement.

Sharing values with one’s employer, meanwhile, was strongly correlated with a range of factors, with those who believed their day-to-day work was relevant to long term goals, those who received ongoing feedback about their work, those who received one-on-one coaching in preparation for new roles and responsibilities, and those who said that use of work-life benefits didn’t affect promotion within their firms most likely to agree that they shared values with their firm. Meanwhile, those who received no training, those without workplace friendships, and those who didn’t know their firm’s performance evaluation criteria were least likely to share values with their company. In short, those with strong, personalized relationships with peers and firm leadership were most likely to see an alignment of values.

Workplace relationships were one of the greatest predictors of workplace culture assessment, with respondents who said that they didn’t have any relationships at work reporting 30% more negative perceptions of their firm culture than those who had workplace friendships. Fortunately, the vast majority of respondents reporting having social relationships at work, with over 70% reporting that they ate lunch or took breaks with coworkers, just over half of respondents reporting that they socialized with coworkers outside of work, and nearly half of respondents reporting that they had close friendships at work. There were slight differences in reported workplace relationships, with women of color least likely to report socializing with coworkers outside of work, and significantly less likely than white women, but slightly more likely than men, to report having close workplace friendships.

Finally, a range of workplace culture initiatives were related to respondents’ perceptions of workplace culture, with respondents reporting that the most effective ways that their firms could promote workplace culture were by organizing social events, by providing space for taking breaks and eating lunch, and by sharing company goals and achievements with employees.

Tenure and Employee Retention

As Maslach and Leiter have shown, these firm culture initiatives and other efforts to keep employees engaged and happy are ultimately important because they impact employee retention. On average, respondents had been with their current firms for 6.8 years. This mean is significantly above the median tenure of three years with a firm, in part because 20% of respondents had been with their firms for 11 years or longer, which pushed the mean higher. Average tenure increased with experience level, with average tenure equalling about half of total years of experience in the field at most experience levels.

While average tenure with one’s current firm was relatively high, we also found that a large number of respondents were considering leaving their current jobs. Overall, we approximately 1 out of 4 respondents reported that they were either somewhat or very likely to leave their firms within the next year.

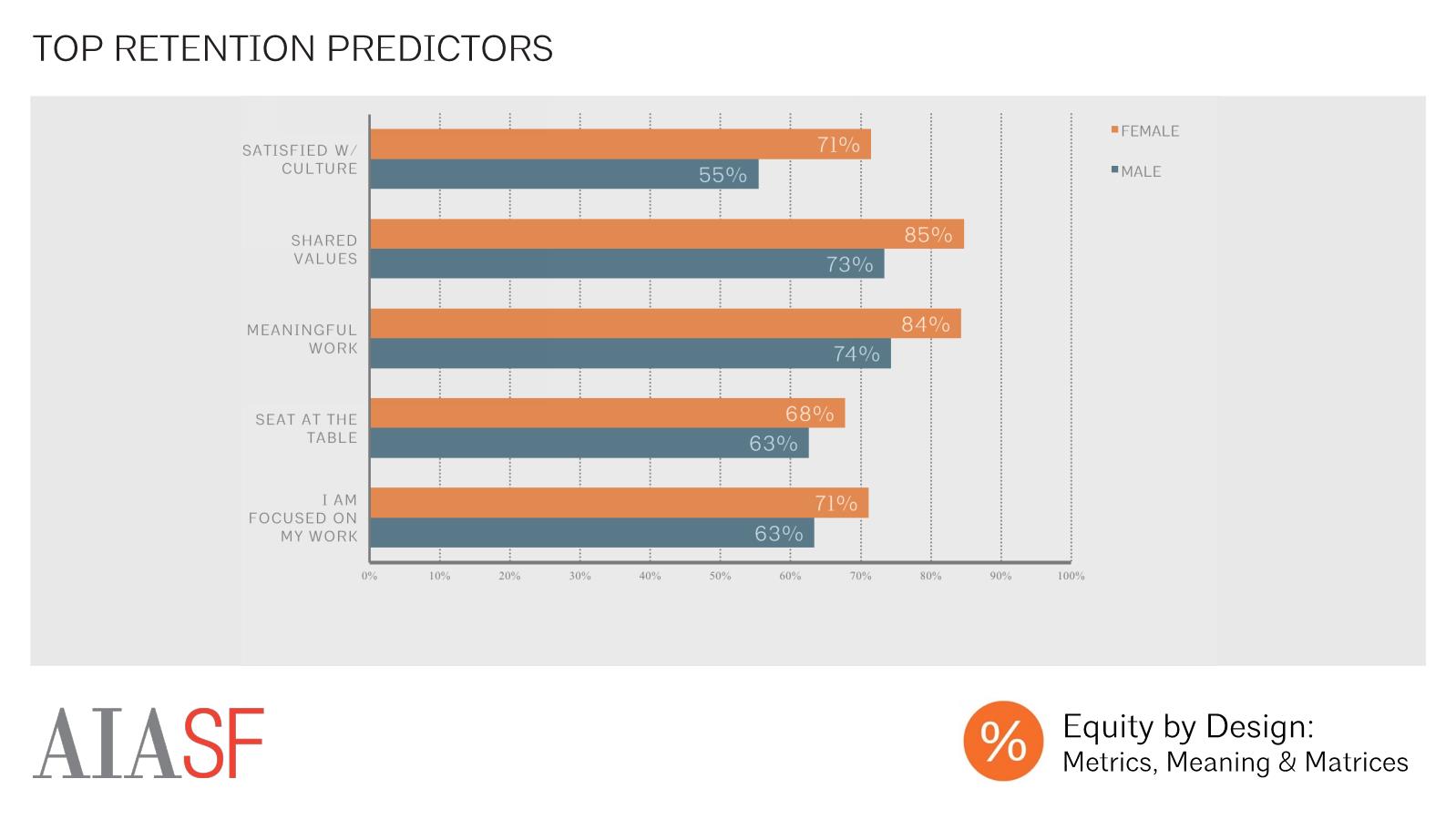

Several factors were strongly correlated with a respondent’s likelihood of planning to remain in their current position, with those who believed that their work was meaningful and rewarding, those who shared values with their company, those who reported feeling involved in their work, those who were given a seat at the table by being included in their firm’s decision-making process, and those who were satisfied with their workplace culture most likely to plan to stay in their current position.