By Annelise Pitts, AIA, Equity by Design Research Chair

We all know the classic work-life narrative in architecture. Long hours and low pay are treated as an integral part of our professional culture. This expectation, we tell ourselves, is fostered in architecture school, where we develop a love of the craft and a sense of community during long nights and even all-nighters spent perfecting projects and bonding with our classmates. This narrative contends that architecture is a discipline that requires persistence, dedication, and countless hours laboring alone over a set of drawings. Real architects, we tell each other, are those who are willing to put all else aside and work seemingly impossible hours to achieve perfection.

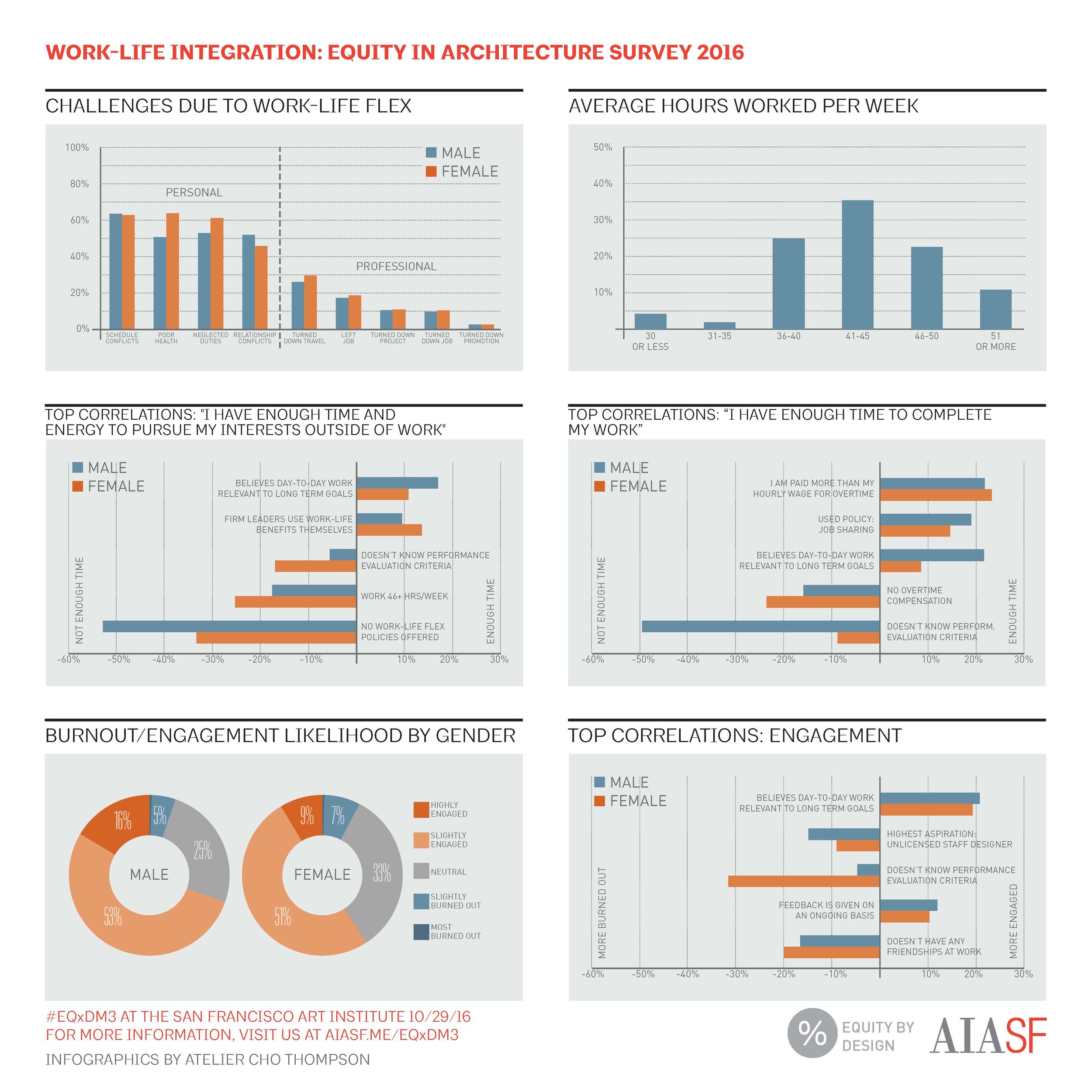

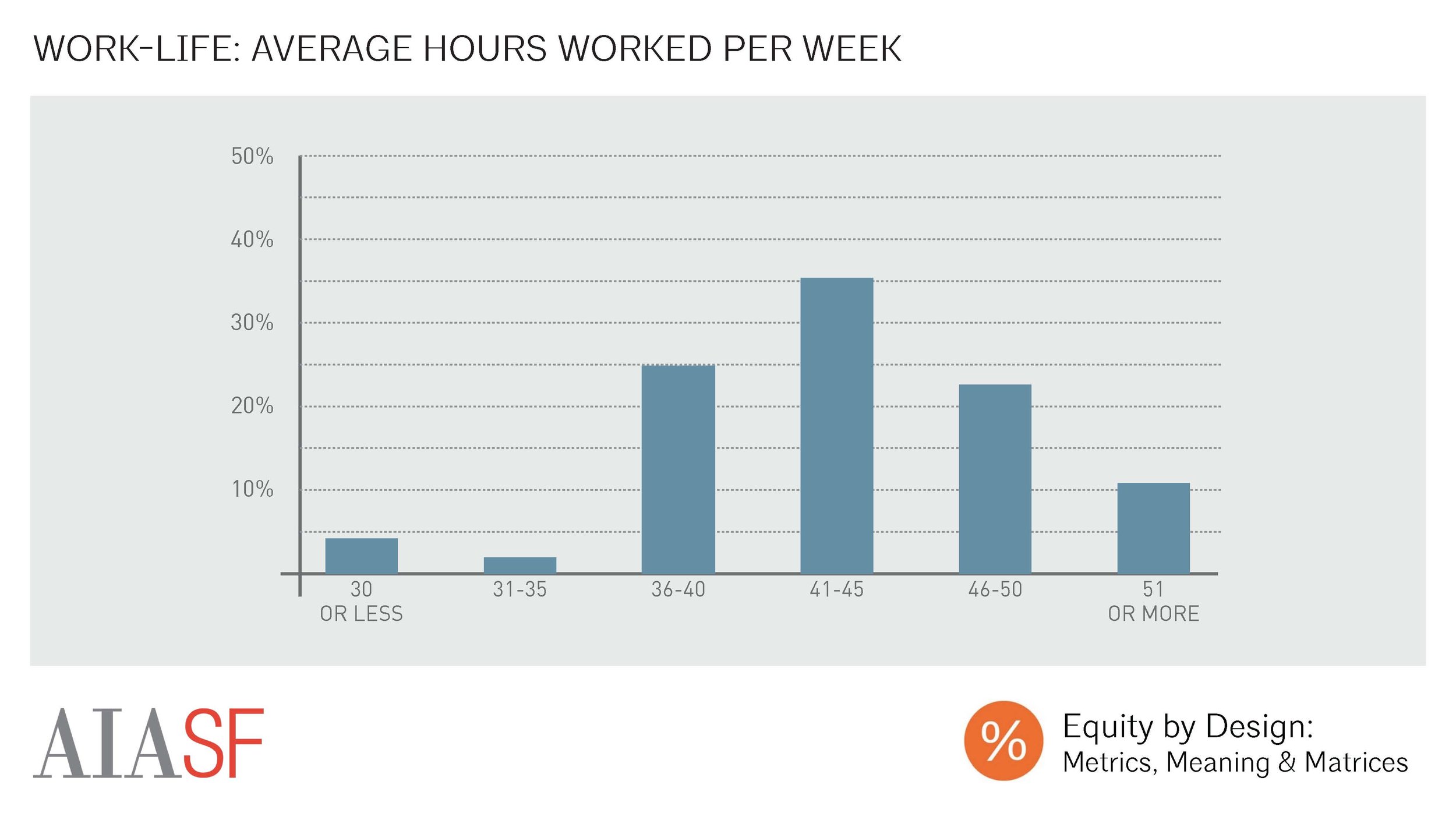

The Equity in Architecture Survey tells a very different story about the state of work-life issues within our profession. According to respondents’ self-reported hours, very few members of our profession work anywhere close to 60 -- or even 50 -- hours in an average week. The vast majority of respondents, both men and women, report that work-life is an important consideration in their careers. Still, a significant majority of respondents report that they have allowed their careers to negatively impact their personal lives, and less than half of respondents report that they are able to find time to pursue personal interests outside of work.

According to these findings, architects are struggling with weekly work schedules that seem very normal when compared to the myth of the workaholic architect. The data suggests that these challenges are strongly correlated a lack of flexibility in where and when we work, in expectations that we will work as much as necessary to meet deadlines, in a lack of understanding of the criteria used to evaluate our performance, in perceived social cues that urge us to work harder or have our professional commitment doubted, and in the absence of meaningful and rewarding work. The “long hours and low pay” narrative that our field has cultivated isn’t damaging because it encourages most architects to work impossible hours, but instead because it masks and delegitimizes the very real struggles that are associated with a much more typical 40-50 hour work week.

Overview

In the metrics below, click over the arrows at the top right above the infographics to see the overview analysis for Work-Life Integration.

Work-life considerations factor strongly into the architectural professionals’ career decisions, regardless of their identity. The vast majority of our respondents report that it was “extremely” or “very important” that their job provided work-life flexibility, integration or balance. In fact, only 4% of men, and 1% or women, believe that these issues were “not too important” or “not important at all.”

While respondents tended to believe that it was important to strike an appropriate work-life relationship, many reported that they had faced challenges in this arena. Women were were more likely to report having faced a host of work-life conflicts, from poor health and neglected personal duties to turning down travel or even leaving a job. It’s also important to note that our respondents, both male and female, were much more likely to report experiencing personal setbacks in the face of work-life conflict than they were to report making professional trade-offs in these situations.

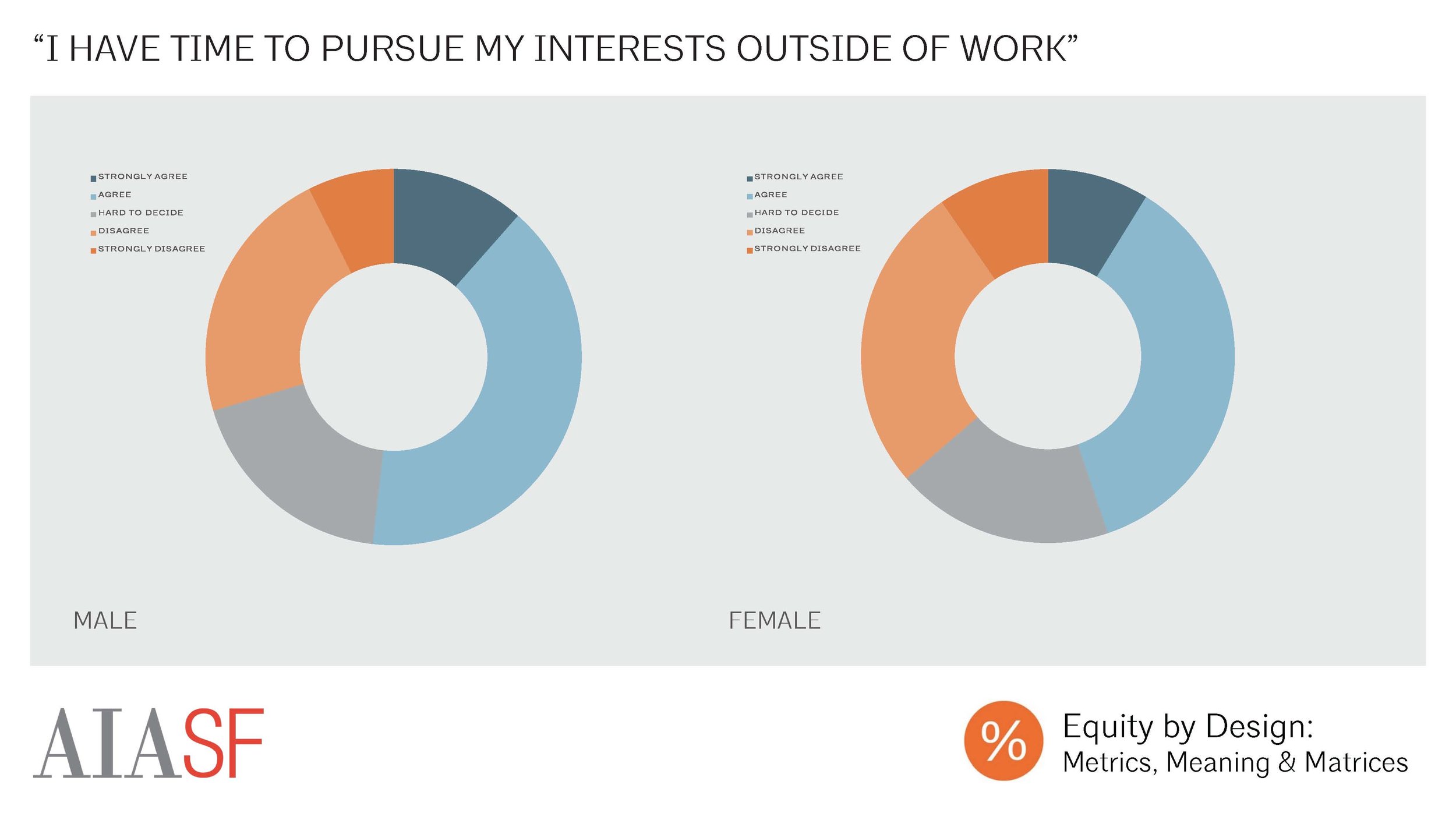

Overall, respondents’ perceptions of their work-life flexibility were relatively low. Just 52% of male respondents, and 45% of female respondents, agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I have enough time and energy to pursue my interests outside of work.”

Similarly, many respondents reported that their workloads were too great, with one in four respondents disagreeing with the statement “I have enough time to complete my work.”

Another way of looking at work-life is by considering burnout and engagement, which are considered to be opposite conditions for the purposes of our data analysis. According to research, burnout is identified by feeling exhausted by one’s work, a lack of focus or involvement in one’s work, and doubting one’s ability to meet expectations. Meanwhile, engagement is characterized by feeling energized by work, feeling involved or focused on work, and believing one has the ability to meet or exceed expectations. Our study showed that most respondents, male and female, were either highly or slightly engaged. Female respondents were slightly more likely than their male counterparts to exhibit signs of burnout.

Key Work-Life Drivers

Clearly, many architectural professionals struggle with work-life challenges, even though most professionals work fewer than 45 hours per week. This suggests that, while it’s important to address extremely long hours, attention should also be paid to the causes of work-life challenge amongst those who are working fewer hours.

When considering each of the indicators of work-life quality used in the survey (ability to pursue interests outside work, availability of time to complete work, burnout/engagement, and history of facing work-life challenge), we found that positive work-life perceptions were predicted by finding one’s work relevant to long-term goals, and working in an environment where work-life flex is encouraged through the clear communication of expectations, the availability of work-life benefits, compensation for overtime work, and leaders who use work-life benefits themselves. Interestingly, these qualitative and cultural factors were more predictive of positive perceptions than any specific policy, or even the average number of hours that a respondent reported working.

In addition to these top predictors, a number of additional factors were found to be correlated with respondents’ work-life perceptions and experiences. Work environment, career pinch points, work schedule and work-life policies and benefits all bear consideration. Please use the arrows on the upper right side of image below to click through the slideshow and learn more.

The top predictors of whether a respondent reported having enough time to pursue interests outside of work were whether they believed their day-to-day work was relevant to long-term goals, and whether their firm’s leaders used work-life benefits themselves. Meanwhile, not knowing performance evaluation criteria, working more than 46 hours a week, and working in a firm without work-life flex policies were associated with negative perceptions of work-life

A respondent’s assessment of one’s workload was another key factor in evaluating work-life flexibility. The top predictors of whether a respondent agreed with the statement “I have enough time to complete my work” were the belief that one’s day-to-day work was relevant to long term goals, being paid more than hourly wage for overtime, and using job sharing. Meanwhile, receiving no overtime compensation, and not knowing performance evaluation criteria were associated with more negative perceptions of workload. Overall, these trends suggest that working in an environment where one’s time is valued -- by making sure that work is relevant to one’s personal goals, and by investing in one’s time either by paying for overtime hours, or by allowing employees to share jobs to allow for part-time schedules -- is critical to managing one’s workload.

The top predictors of burnout were not having friendships at work, aspiring to be an unlicensed staff designer, and not knowing the criteria for performance evaluation. Meanwhile, believing day-to-day work was relevant to long-term goals and receiving feedback on an ongoing basis were associated with higher levels of engagement.

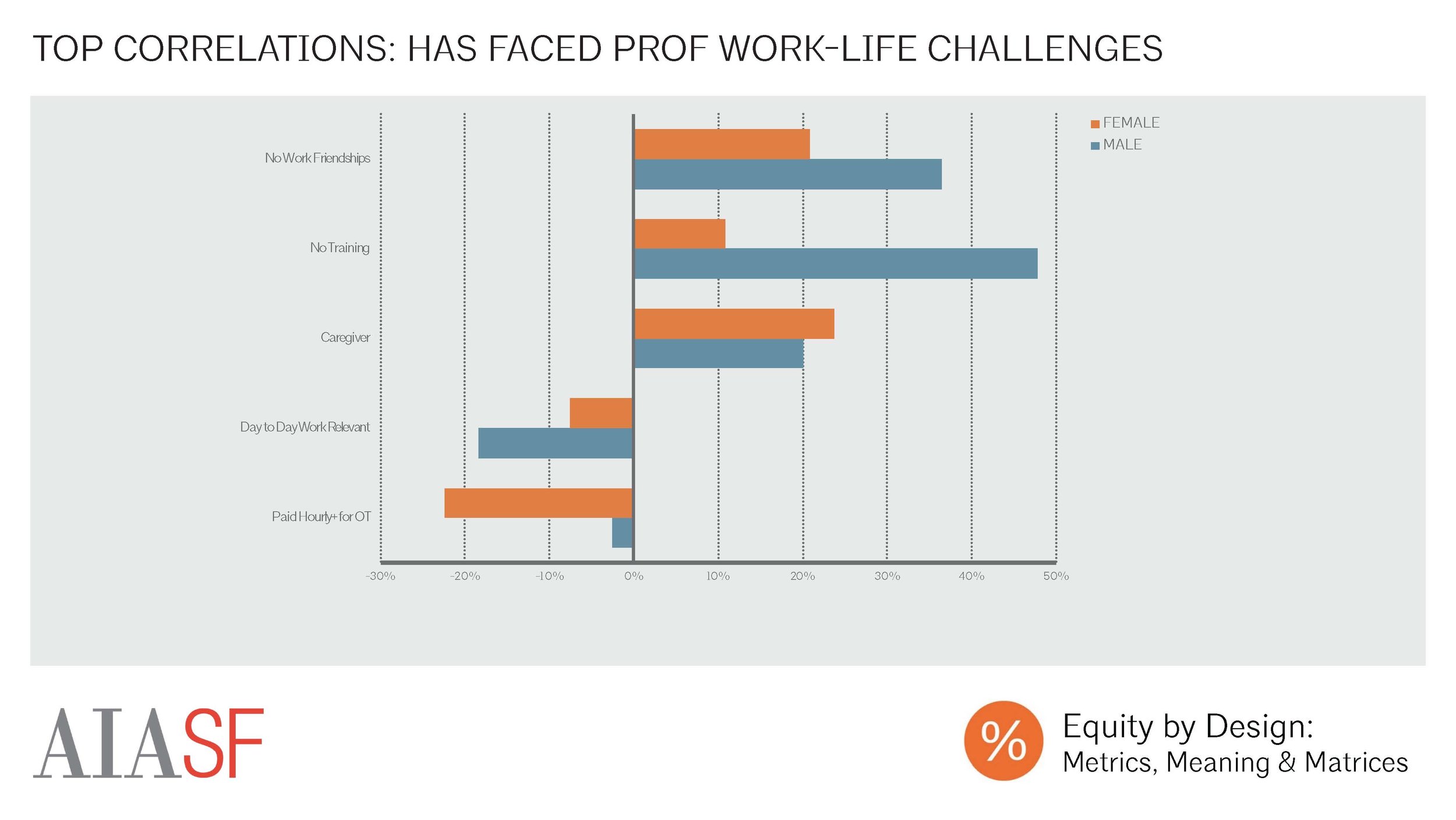

Overall, the top predictors of whether a respondent reported having made personal trade-offs in the face of work-life challenges were working 46 or more hours per week, being expected to work as much as necessary to meet deadlines, and being paid more than one’s hourly wage for overtime. Meanwhile, having access to in-house or subsidized daycare and reporting that one never worked overtime were associated with decreased likelihood of personal trade-off. In short, workplaces that incentivized or created expectations of overtime were associated with increased likelihood of making sacrifices in one’s personal life in the face of work-life challenge.

Meanwhile, the top predictors of whether a respondent reported having made professional trade-offs in the face of work-life challenges were having no friendships at work, not receiving training for new roles, and being a caregiver. Those whose day-to-day work was relevant to their long-term goals, and those who were paid more than their hourly wage for overtime were less likely to have made personal trade-offs.

The size of a respondent’s firm was correlated with work-life perception, with respondents who worked in the smallest firms much more likely than those working in the largest firms to agree with the statement “I have the time and energy to pursue my interests outside of work” (55% M| 50% F in XS firms vs. 39% M| 33% F in XL firms). There were not strong correlations between firm size and whether a respondent reported having time to complete their work, exhibited signs of burnout, or had faced work-life challenges in the past.

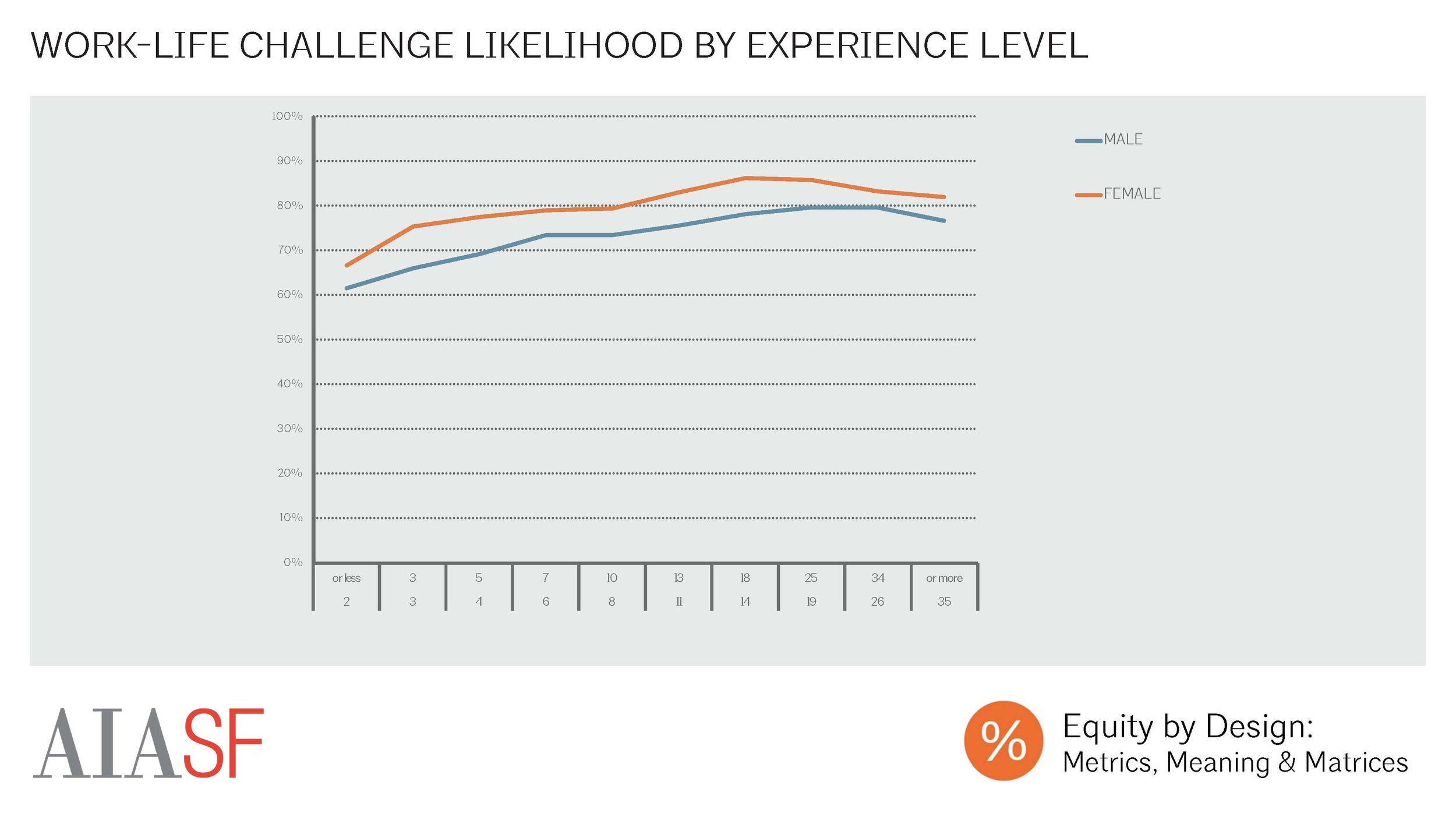

Experience level was a significant factor in predicting a respondent’s work-life prioritization and experiences. Those in the middle of their careers were more likely to value work-life flexibility than either those entering the field or the most seasoned professionals, with over 60% of women with 14-18 years of experience indicating that work-life considerations were “extremely important” to them.

While women placed a higher value on work-life flexibility than men at every level of experience, this gap was at its narrowest amongst those early in their careers. This is largely because because junior and mid-level male respondents valued work-life flexibility much more than their more senior counterparts. This suggests that, at least for the younger generations, work-life flexibility is an important issue for all genders.

While work-life flexibility was most important to those with 10-20 years of experience, this was also the career stage at which respondents were least likely to believe that their workloads were manageable. Less than half of respondents with 10-25 years of experience believes that they had enough time to complete their work.

Similarly, those with more experience were more likely than those early in their careers to report that they had faced work-life challenges in the past. Because this question asked whether a respondent had ever faced these challenges, and not whether the respondent was currently facing them, it is somewhat unsurprising that those with the longest career histories were most likely to report facing challenges. The prevalence of these challenges was, however, staggering - 79% of men, and 86% of women, with 14-25 years experience reported that they had made either personal or professional trade-offs in response to work-life challenges.

Promoting a Positive Work-Life Relationship

Firms have a role to play in shaping their employees work-life experiences. A number of factors, from how hours are determined to whether employees are allowed or even encouraged to take time off, were correlated with respondents’ work-life perceptions and experiences. Please use the arrows on the upper right side of image below to click through the slideshow and learn more.

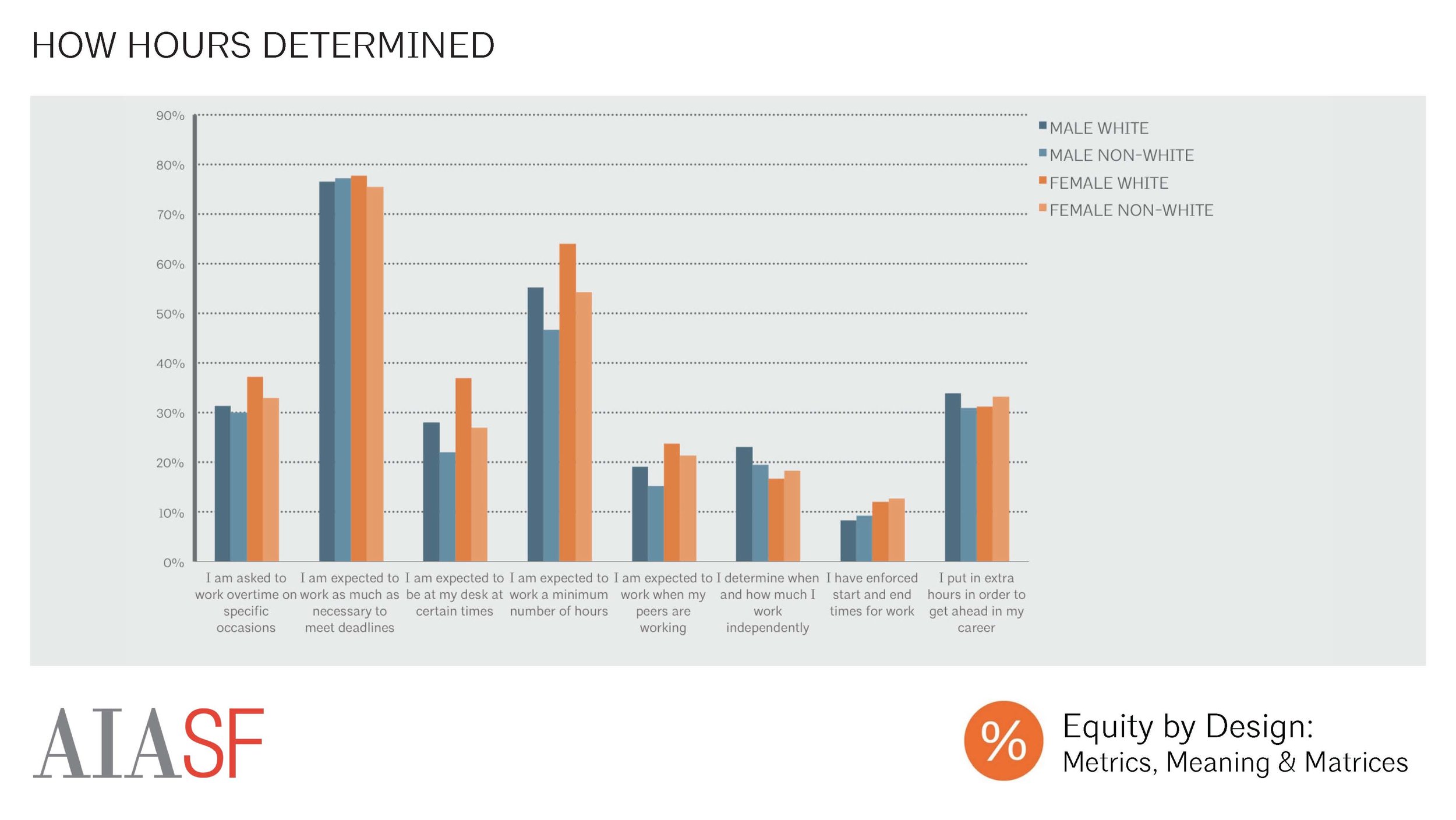

Respondents’ work schedules were determined in a variety of ways. The majority of respondents (77%) reported that they were expected to work as much as necessary to meet deadlines, suggesting that irregular schedules, with peaks in working hours around deadlines, and less hours at other times, might be the norm for architectural professionals. Compared to those whose hours were determined in another way, those who reported that they were expected to put in as many hours as necessary to meet deadlines were 12% less likely (-12% M | -13% F) to believe that they had time to pursue their interests outside of work, 11% less likely to believe that they had enough time to complete their work (-12% M | -10% F), and 13% more likely to have faced work-life challenges (16% M | 11% F).

While potentially long hours were expected of most respondents as needed to meet deadlines, few received compensation for overtime work. Overall, 59% of practitioners reported that they were not compensated in any way for overtime work. White men were least likely to be compensated for overtime work, potentially because white male respondents were more experienced on average, and were more likely to be salaried (vs. hourly) employees. Of those who were offered compensation for overtime work, comp time, or regular business hours off in exchange for overtime hours worked, was the most common form of compensation. Only 23% of respondents received monetary compensation, whether in their paycheck or through a bonus, for overtime work.

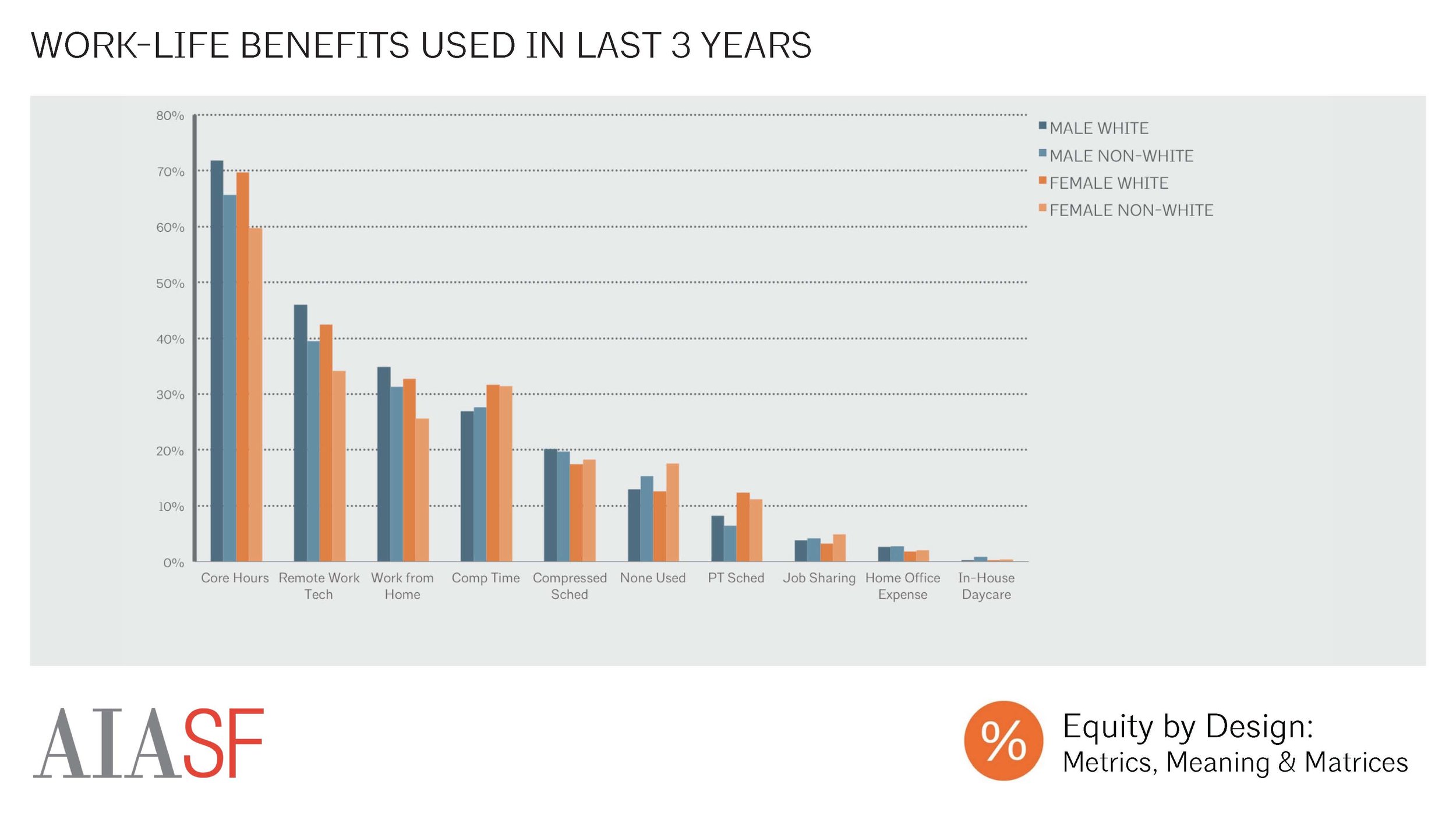

According to respondents, firms are offering a variety of benefits and policies intended to to promote work-life flexibility. Most respondents reported that they had flexibility in terms of start and end times for work (“core hours”), and firm-provided technology to support working from home. Other common work-life benefits included the ability to work from home during normal business hours, comp time (time off in exchange for overtime hours worked), part time schedules, and a compressed schedule (40+ hours/week, with more than 8 hours on some days of the week, and a regularly scheduled full, or partial day off). White male respondents were more likely than women and people of color to report having access to every one of these work-life benefits.

The vast majority of respondents reported that they had used work-life benefits within the last three years, but there was a great deal of variety in terms of which work-life benefits respondents reported using. White males were also more likely than others to report using the three most commonly offered work-life flexibility benefits (core hours, technology to support remote work, and working from home). People of color were less likely than white respondents to report using each of the most common benefits. Female respondents, meanwhile, were more likely than male respondents to use comp time.

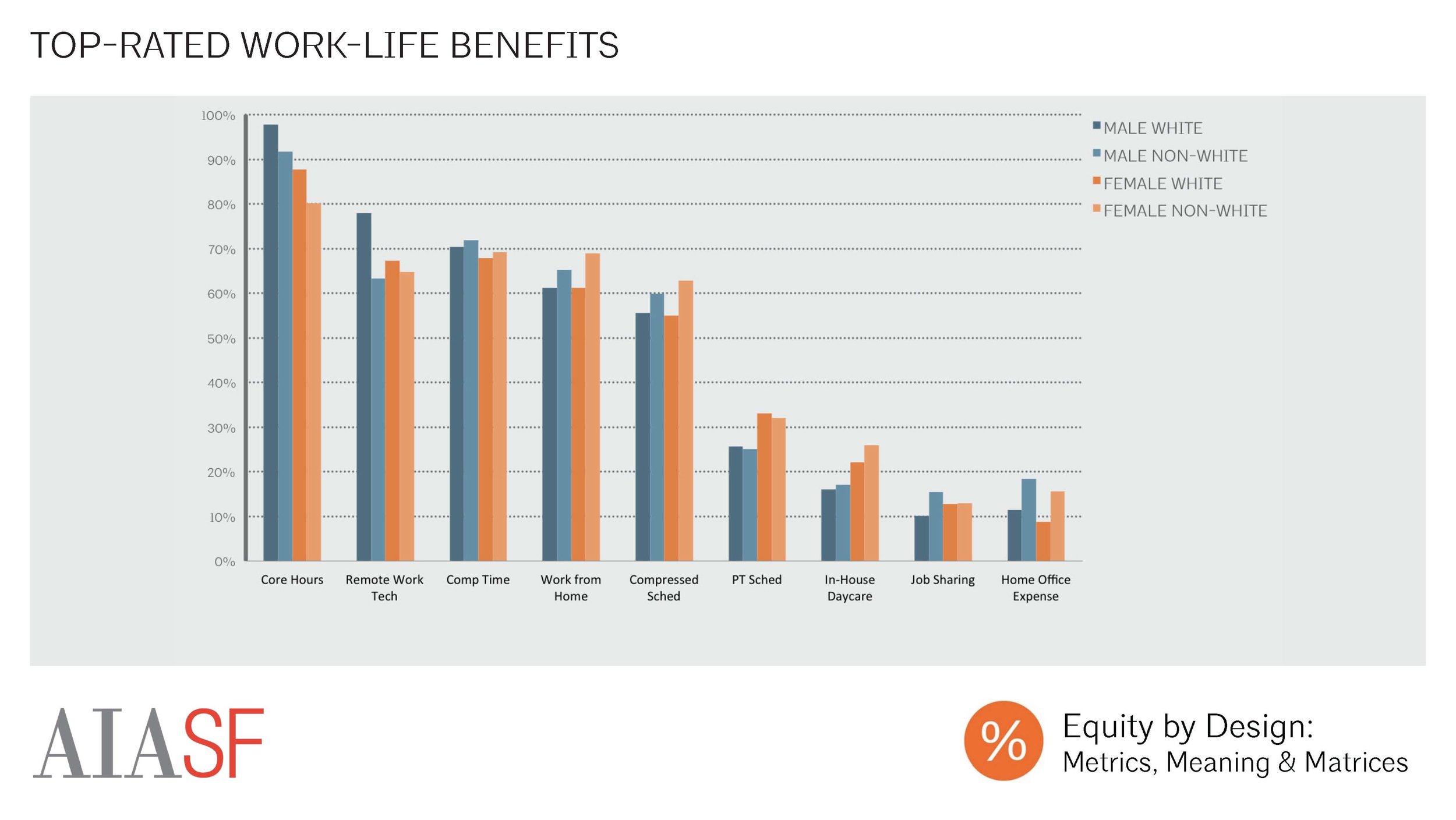

When asked which benefits were most helpful in promoting work-life flexibility, the most common responses were: “core hours,” “technology to support remote work,” and “comp time.” in other words, respondents most likely to value benefits that offered them flexibility in terms of where and when they worked, rather than benefits that allowed them to work less hours overall.

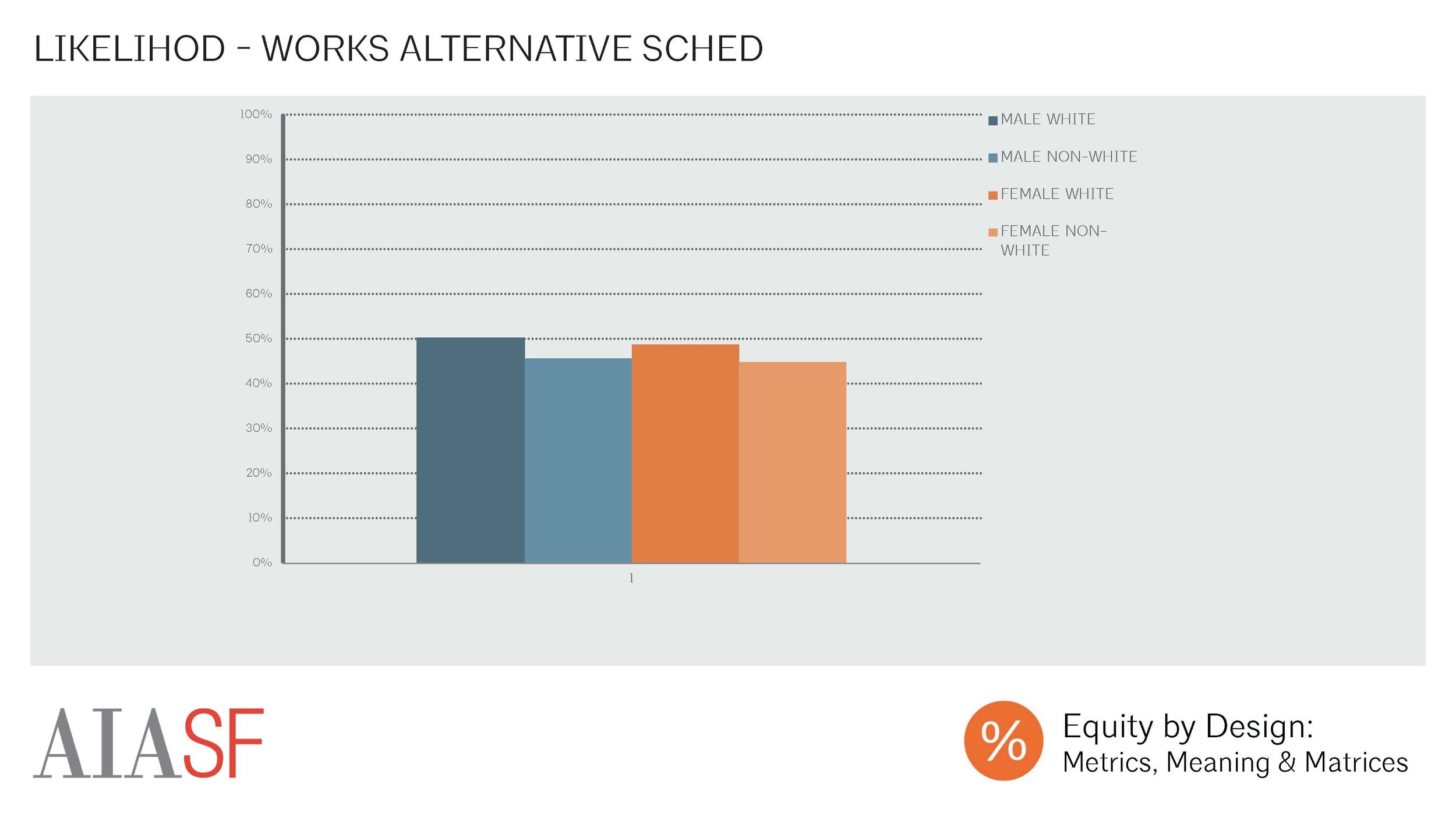

Overall, 49% of respondents reported having worked some kind of alternative schedule over the last 3 years. For the purposes of our analysis, the following types of schedule were considered “alternative”: compressed (40 hours/week, with some days longer than 8 hours, and some days with fewer or no hours), telecommuting (working from home during regular business hours), part time (less than 40 hours per week), and job sharing (two or more people work part time hours to do the equivalent of one full-time employee’s workload). There wasn’t much variation in likelihood of working an alternative schedule, but white men were actually slightly more likely than other respondents to have worked an alternative schedule. The most common type of alternative schedule was working from home, while job sharing was the least common.

The most common reasons that respondents reported working alternative schedules were overall flexibility, increased productivity, and to pursue personal interests. Female respondents were more likely than male respondents to report working an alternative schedule in order to provide childcare.

Overall, most respondents who worked an alternative schedule reported that the schedule hadn’t had any adverse impacts on their career. White men were least likely to report adverse impacts, while non-white men, white women, and non-white women were each successively more likely to report adverse impacts.

The most commonly reported adverse impact was a belief that co-workers perceived alternative schedule users as less committed to their careers. Women who had worked alternative schedules were twice as likely as men who worked these schedules to report this adverse impact.

Respondents’ perceptions of the ways in which their alternative schedules had impacted their careers varied by alternative schedule type. Part-time schedules were associated with the highest probability of believing that one’s schedule had adversely impacted one’s career, with less than half of respondents reporting no impacts. Women were much more likely than men to report being adversely impacted by their schedules (65 % of men reported no impacts vs. 36% of women). The most common reported impact of working part time was a reduced rate of compensation.

Amongst our respondents working in firms, we found that it was relatively rare to have taken off a month or more in the past, either by taking a leave of absence, or by leaving a job entirely.

However, amongst those who had never taken this time off, we found that only 31% of our male respondents, and just 19% of our female respondents had never wanted to do so, and didn’t anticipate wanting to take a month or more off in the future. With so many practitioners hoping to take time away from a job in architecture, employers would do well to consider sabbatical or leave of absence programs.

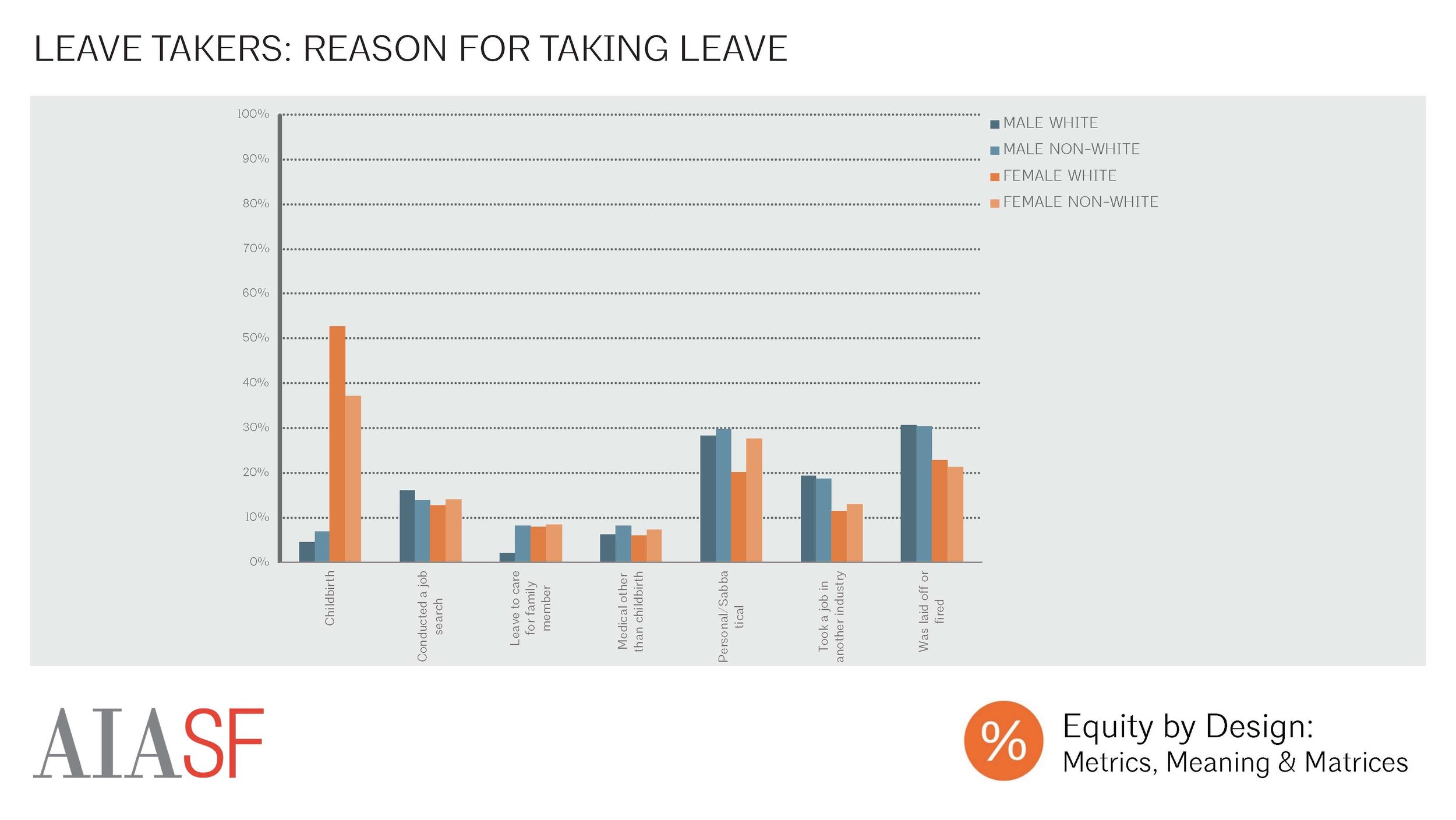

Amongst those who had taken a leave, the most common reasons were childbirth, having been laid off, and taking a personal leave or sabbatical. Women were much more likely to have taken a leave for childbirth, with 53% of white female leave-takers, 37% of non-white female leave-takers, 7% of non-white leave-takers, and 5% of white leave-takers reporting taking a month or more for childbirth.

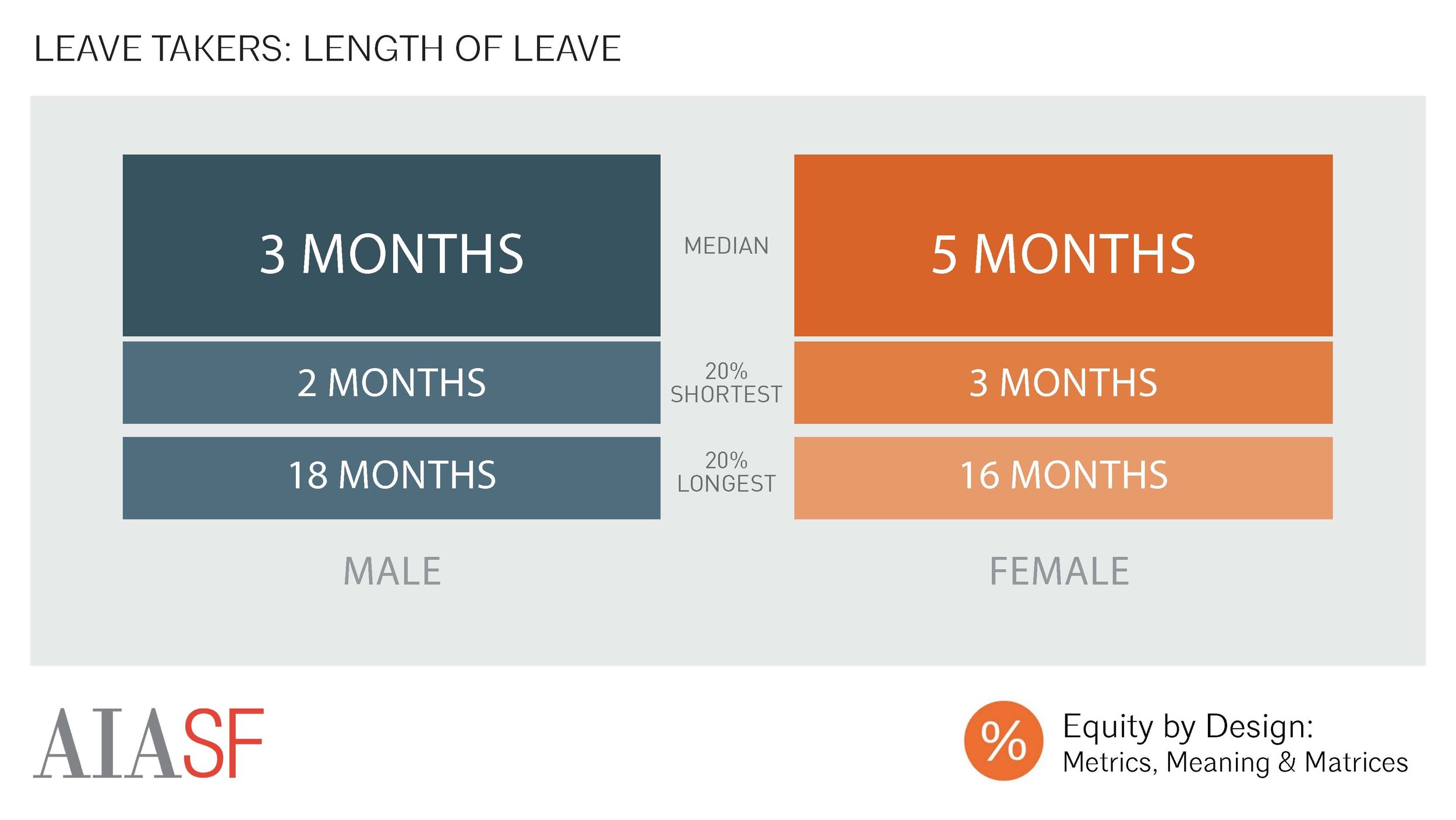

There was considerable variation in the amount of time that leave-takers spent away from the field, with a 20th percentile leave length of 2 months, a median leave-length of 5 months, and an 80th percentile leave length of 18 months. Male respondents took slightly shorter leaves, on average, than female respondents.

White male leave-takers were much more likely than women and people of color to report that their leaves had caused no adverse impacts on their careers (59% of White Males | 52% Non-White Males | 43% White Females | 41% Non-White Females). The most commonly reported adverse impacts were delayed advancement or promotion and reduced rates of compensation.

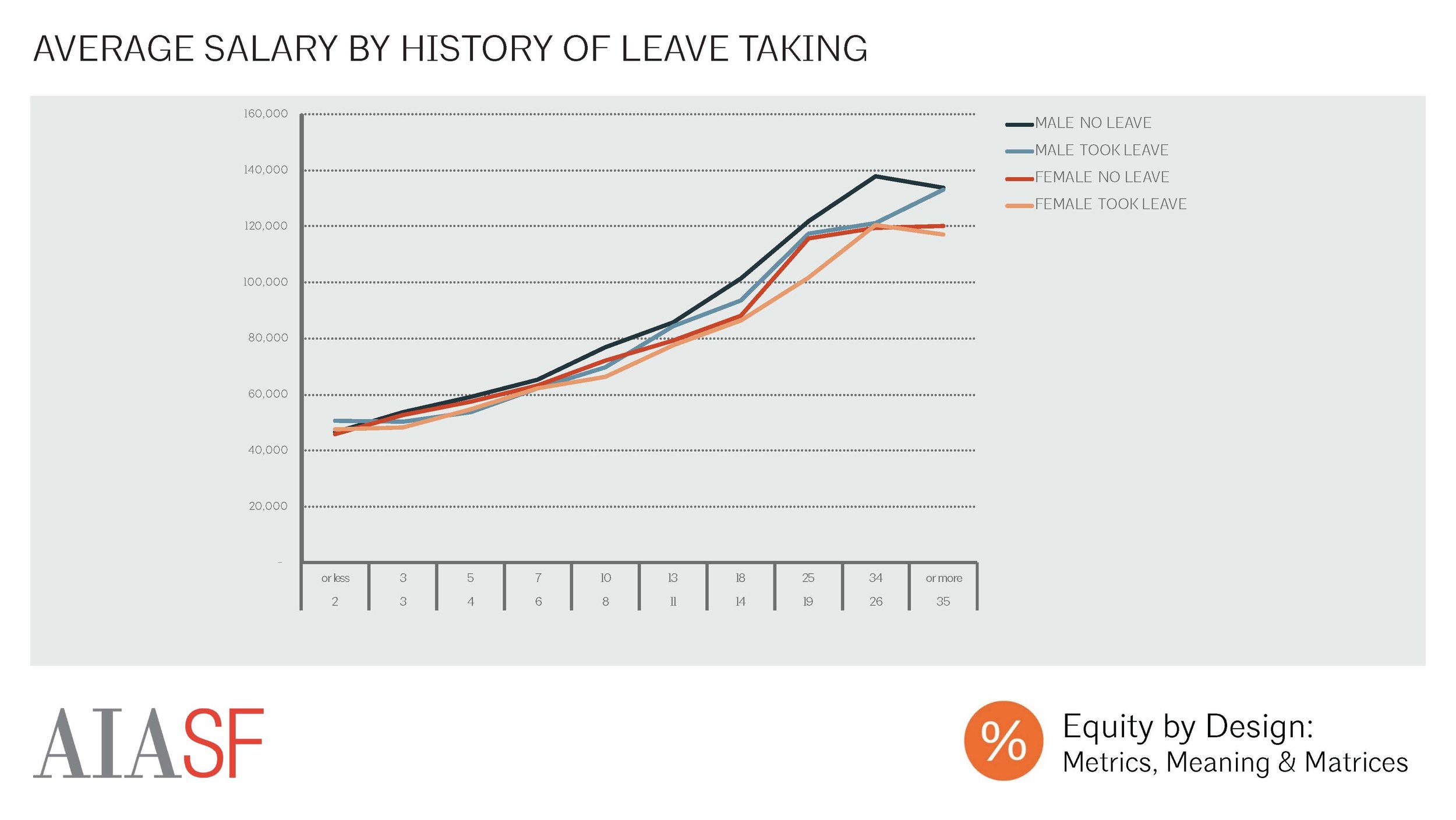

A history of leave-taking was also correlated with measures of professional success like salary and compensation. Men who had taken a leave in the past made less, on average, than those who had never taken time away. Similarly, women who had never taken a leave in the past made more on average than those who had taken a leave.

Meanwhile, women who had never taken a leave were much less likely than leave-takers at nearly every level of experience to be a principal or partner. Amongst those with more than 13 years of experience, men who had never taken a leave were more likely to hold these leadership positions.

There were no significant differences in career perceptions amongst leave-takers and those who had never taken a leave.

Key Take-Aways

Work-life considerations factor strongly into the architectural professionals’ career decisions, regardless of their identity. The vast majority of our respondents reported that it was “extremely” or “very important” that their job provided work-life flexibility, integration or balance.

Work-Life perceptions were strongly correlated with gender, with women much more likely to report having faced work-life challenges, and less likely to have time to pursue personal interests outside of work.

Access to, and utilization of, work-life benefits was strongly correlated w/ both race and gender, with non-white respondents less likely to have access to these benefits than white respondents.

Work-Life considerations were often most important for those with 10-20 years of experience, but industry response hasn’t met demand. This group utilized work-life benefits at the highest rate of any group, but still struggled with low levels of satisfaction with their workloads, and their work-life flexibility.

Work Environment was also strongly correlated with at least some work-life considerations, with those in the largest firms expressing the lowest satisfaction w/ their ability to pursue interests outside of work.

Most importantly, the strongest predictors of work-life experience were related to workplace culture: we found that positive work-life perceptions were predicted by finding one’s work relevant to long-term goals, and working in an environment where work-life flex is encouraged through the clear communication of expectations, the availability of work-life benefits, compensation for overtime work, and leaders who use work-life benefits themselves.