By Kendall Nicholson, Ed.D., Director of Research and Information at Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture

When we think about diversity in architectural education many of us think about the people: the students, the faculty and the administrators. This, however, is not the subject of this post. In lieu of diversity as evaluated on the premise of gender or ethnicity, I'd like to discuss diversity within architectural curricula. On the whole, architecture programs vary widely in their areas of expertise (see Index of Scholarship), program type (see Study Architecture) and their overall program philosophy (i.e. where they fit on the art-science continuum). Each school's philosophical approach directly affects the courses selected to create the school's curriculum. Consequently, some schools embellish the liberal arts, some encourage the exploration of technology and others forward environmental concerns.

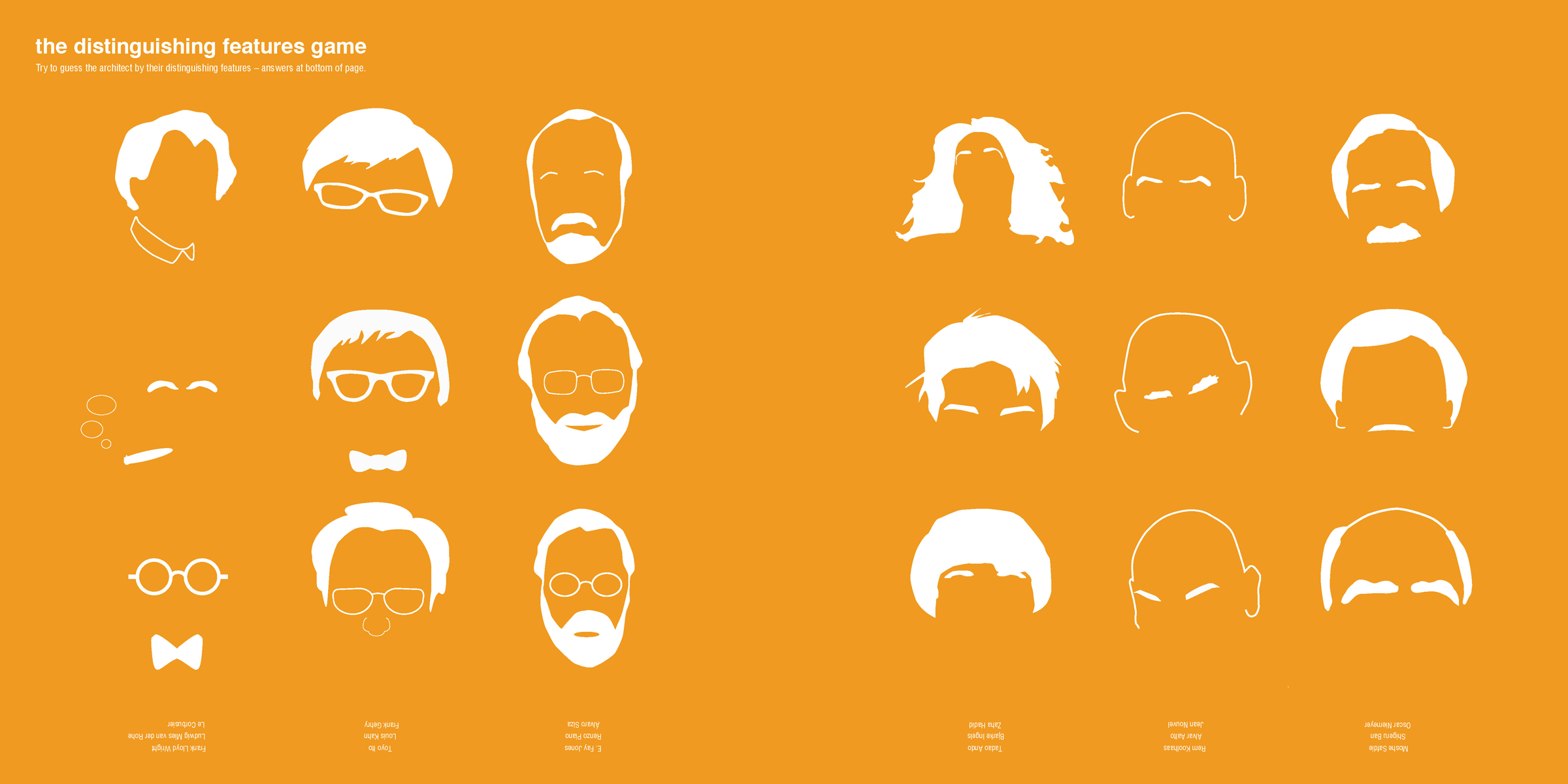

As the Director of Research and Information at the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), I have had the privilege of conversing with faculty from schools across the nation. As schools continue to examine their curricula, one area often lacking diversity is architectural history and theory. Figures like Vitruvius, Thomas Jefferson, and Le Corbusier are often the subject of discussion in courses required across the country. As a result, architectural history and theory in the U.S. has been traditionally European, male and modern. And this is where we find implicit bias. While these names should be part of the body of knowledge, I would argue that an architect's required awareness of history and theory should be more expansive. By excluding architecture found in non-European cultures, the curriculum, perhaps inadvertently, communicates that they are of less importance. Additionally, these curricula often fail to recognize the contributions of female architects and designers. As the architecture student body continues to morph into one that represents modern America, the mandate for inclusive history and theory coursework becomes all the more important.

The National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB), ACSA and many architectural programs are taking steps forward to diversify their history and theory curriculum. The latest edition (2014) of student performance criteria issued by NAAB requires programs to ensure students have an understanding of “History and Global Culture” as well as “Cultural Diversity and Social Equity.” This is a significant evolution from the 2004 requirement that students demonstrate an understanding of “Western Traditions” and “Non-Western Traditions.” Additionally, the ACSA Education Committee is developing resources and identifying best practices to increase demographic diversity. Included in this charge is an examination of school curricula, with the hopes of making course content more relevant to underrepresented students.

In recent years schools have started to change their curricula. Louis Nelson, Professor of Architectural History at the University of Virginia, teaches courses like “World Vernacular Architecture” that feature examples from Cambodia and Morocco in addition to his longstanding research of the West Indies. Per his syllabus, Amir Ameri, Associate Professor at the University of Colorado Denver, makes an intentional effort in his History of Architecture I course, to supplement the textbooks with “required readings on architecture of the Middle East, East Asia, Americas and Africa.” In 2014, Princeton University launched the Princeton-Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism and the Humanities. This project hosts a number of courses exploring the architecture of North and South American cities with a strong emphasis on Latin America. Moreover, the University at Buffalo, SUNY offers courses like “American Diversity and Design” which analyzes U.S. history using design theories surrounding race, ethnicity, gender, class, age, physical ability, cognitive ability, and religion. These are only a few examples of the shift happening in curricula across the country. Despite the current political climate, ACSA makes a commitment to championing inclusion and will continue to advocate for addressing the hidden biases that challenge the context of architectural education.